A lot of the predictions we hear about the future involve a hot, crowded planet, one where we need some serious science to figure out how to feed everyone and control rising global temperatures. The UN’s population forecast of almost 10 billion people by 2050 is widely quoted, and with it has come much conjecture about what such a world will look like. Where will all those people live? What kind of jobs will they have? What will they eat?

But before we invest too much into preparing for an impending population boom, we should consider some factors that, though often overlooked, could have a massive impact on the world’s population 20, 30, and even 80 years from now. A paper published in The Lancet explores the impact on population of factors like fertility, mortality, and migration, and details potential deviations from a heavily-populated future Earth.

On top of forecasting the populations of 195 countries, the study looked at age demographics and the impact they could have on national economies and the global power structure.

“Continued global population growth through the century is no longer the most likely trajectory for the world’s population,” said the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Director Dr. Christopher Murray, who led the research. “This study provides governments of all countries an opportunity to start rethinking their policies on migration, workforces, and economic development to address the challenges presented by demographic change.”

Here are some of the paper’s key findings, and what they could mean for the future of our countries, economies, and planet.

How Many People Will There Be?

The study predicts that the global population will peak at around 9.7 billion, but not until 2064. By the end of the century in 2100, that number will plummet by almost a billion people, to 8.8 billion.

It’s a pretty huge fluctuation in 35 years’ time, especially barring events that would take out a big chunk of people at once, like world wars, natural disasters, or pandemics. According to the research, though, 23 countries will see their populations shrink by more than half, including Japan, Thailand, Italy, and Spain.

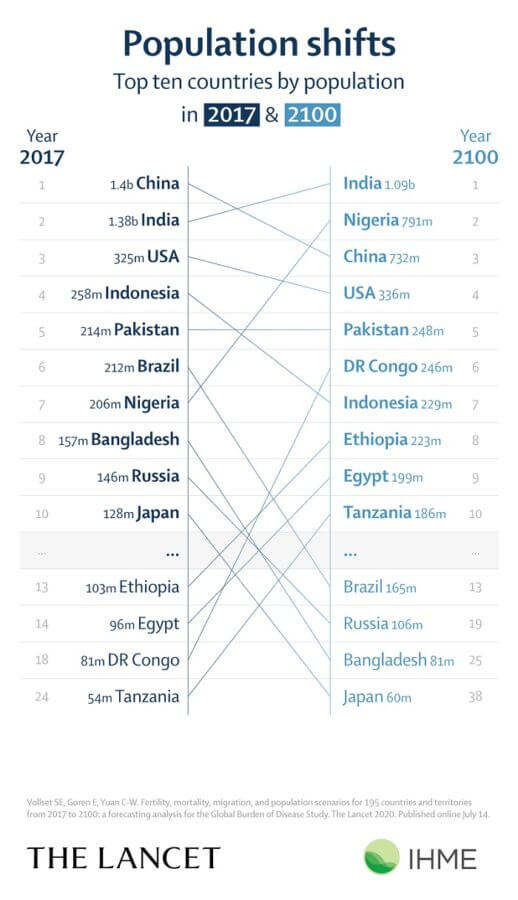

The US would reach its projected peak of 364 million people in 2062, then fall to 336 million by 2100. This would make the US the world’s fourth most populous country after India, Nigeria, and China, in that order, followed by Pakistan in fifth place. China’s population is expected to shrink to 732 million by 2100, while Nigeria’s is set to explode, more than tripling from its current 206 million to 791 million by 2100. Sub-Saharan Africa’s total population is also forecast to triple, reaching 3.07 billion by 2100.

How Will the Global Economy Change?

The percentage of a country’s population that’s of working age—defined by the OECD as 15 to 64—has a significant impact on its economy. It’s part of why China was able to spur such a massive change in its GDP and poverty rates in just 30 years; high birth rates before the country’s one-child policy meant the opening of China’s economy coincided perfectly with a huge working-age population. It’s also why Japan’s aging population could be called a “demographic time bomb.”

The IHME study predicts major shifts in the global age structure, with far more old than young people by 2100; it estimates there’ll be 2.37 billion people over 65 and only 1.7 billion under 20. Moreover, the countries with the most young people will be those that are currently poorer, and their large working-age populations should accelerate their GDP growth.

IHME Professor Stein Emil Vollset, first author of the paper, said, “Our findings suggest that the decline in the numbers of working-age adults alone will reduce GDP growth rates that could result in major shifts in global economic power by the century’s end.”

At the moment, tensions between China and the West seem to be mounting, with multiple countries recently moving to ban Chinese companies like Huawei and TikTok; meanwhile, China is steadily advancing in technologies like AI and genetic engineering. The US and China are, in a sense, vying for global dominance, and the international leadership vacuum left by the current US administration’s foreign policy isn’t helping.

The study predicts China will overtake the US economically by 2035, but if the US maintains a liberal immigration policy, it will go back to having the world’s biggest economy by 2098.

The emphasis on immigration as an economic bolster here is critical. Countries that promote liberal immigration, the paper says, are better able to maintain their population size and support economic growth, even in the face of declining fertility rates.

“For high-income countries with below-replacement fertility rates, the best solutions for sustaining current population levels, economic growth, and geopolitical security are open immigration policies and social policies supportive of families having their desired number of children,” said Murray.

It’s crucial, though, that countries put women’s rights, education, and healthcare ahead of population growth; we already saw what happens when a government tries to force women to have as many children as possible, and it wasn’t pretty.

The Fertility Factor

According to the paper, the UN uses trends from the past to predict how fertility and mortality will evolve across countries in the future. But it leaves out one huge influencer: the fact that there’s not only room for improvement, but improvement is likely.

Though it may not seem like it right now—Covid-19 has thrown a big wrench in all kinds of statistics regarding both the present and the future—human well-being has been on a steady upward trajectory for the past couple decades. Infant and maternal mortality are down. Life expectancy is up, and gender equality is progressing. The widespread dissemination of technologies like smartphones, combined with government policies aimed at helping the most vulnerable, are lifting people out of poverty.

These trends are likely to continue and even accelerate, and as further gains are made in gender equality and access to education, one of the biggest knock-on effects we’ll see is fewer babies.

At present, women in poor countries are far more likely than women in rich countries to start having babies young, and to have a lot of them. This is due to cultural factors, like marrying young, as well as lack of education and access to contraceptives. The IHME research accounted for the likelihood that women will continue to have greater access to education and reproductive health services, and as a result will delay childbirth and have fewer kids.

The difference between this study’s projections and UN forecasts, then, come mainly from the associated decline in fertility rates. The team predicts that in sub-Saharan Africa there will be 702 million fewer people by 2100 than UN forecasts predict, and over 1 billion fewer in south and southeast Asia.

Less Is More?

Despite advances in technology that include bigger agricultural yields, cheaper manufacturing, and closely-linked global supply chains, the resources available to us do have a limit, and fewer people means more resources per person.

Looking again to China’s example, the country was in part able to achieve its astounding economic growth and decline in extreme poverty due to its one-child policy. The Chinese population grew just 38 percent from 1980 to 2013, while India’s grew by 84 percent and Sub-Saharan Africa’s by 147 percent in the same time period. Fewer mouths to feed means more food per mouth, more wealth per capita, and more people having their needs met.

This applies on a global scale, too, and the paper’s authors point out that their forecasts have positive implications for the environment, climate change, and food production—though they acknowledge the predictions could have negative implications for labor forces, economic growth, and social support systems in the countries with the biggest fertility declines.

Humans are pretty good at adapting, though. Whether learning to stay inside for three months straight to curb the spread of a disease or figuring out how to cope with a smaller working-age population, odds are, we’ll manage. A lot can change between now and the year 2100, but from our current vantage point, having fewer than 10 billion people on Earth doesn’t sound too bad.

This article originally appeared on Singularity Hub, a publication of Singularity University.