Nurses are heroes of the COVID-19 crisis. May 12 is International Nurses Day, which commemorates the birthday of Florence Nightingale, the first “professional nurse.” The World Health Organization also named this year the “Year of the Nurse” in honor of Nightingale’s 200th birthday.

To nurses everywhere, this day and this year have great significance. Nurses, who are being recognized as heroes, have long awaited recognition as health care professionals in their own right and not ancillary to physicians. It’s wonderful to be recognized now in the context of coronavirus, but nurses have always been at the forefront – during war, epidemics and other times of disaster.

I have been a nurse for 40 years and a nurse practitioner for 17 of those years. An active clinician, researcher, scholar and educator, I currently serve as dean of the Solomont School of Nursing at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. Throughout my career, nurses have typically been relegated to a secondary role, and if mentioned at all, we are described as assisting doctors. Nurses today are still asked why they didn’t become doctors instead. Aren’t we smart enough?

Many people don’t realize that nursing and doctoring are entirely different professions with different purposes. We are proud to work alongside doctors and other health professionals, but we have never worked behind them. Not all nurses work at the bedside, but we all touch the lives of patients.

Many nurses have doctoral degrees. They conduct research that advances the quality of patient care. Nurses change health care policy. For example, nurses play a significant role in health care reform and advise Congress on proposed health care rules and regulations. They also guide organizations regarding health care technology and care coordination and sit on executive boards of health care organizations. Nursing is both an art and a science.

The role of the nurse has evolved, but some things haven’t changed. Nurses have always cared for the sick, the well and the dying. We promote health and prevent illness. We interpret what is happening so that patients understand it. We are there for the entire patient experience from birth to old age, from wellness to illness, and throughout age and illness toward a peaceful and dignified death.

Our history provides many examples.

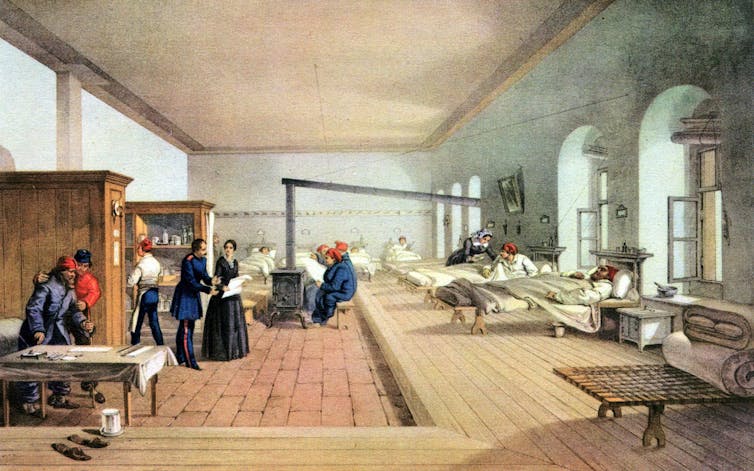

In 1854, Florence Nightingale brought 38 volunteer nurses to care for soldiers during the Crimean War. The cause of the conflict focused on the rights of Christians in the Holy Land and involved Russia, the Ottoman Empire, France, Sardinia and the United Kingdom. Male nurses provided care as far back as the Knights Hospitaller in the 11th century. But prior to Nightingale’s involvement, male and female nurses consisted of untrained family members or soldiers who cared for the ill and infirm.

Nightingale was the first to organize nurses and provide standardized roles and responsibilities for the profession. As such, she is credited with founding modern professional nursing. She was also an expert statistician, collecting data on patients and what did and didn’t work to make them better. Nightingale and her nurses improved sanitation, hygiene and nutrition. They provided care and comfort. Their work had a major impact on the survival of soldiers.

The American Civil War in the 1860s brought thousands of trained nurses to the battlefront, risking their lives to care for soldiers on both sides of the conflict. The most famous were Dorothea Dix, an advocate for indigenous populations and the mentally ill; Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross; and Louisa May Alcott, the author of “Little Women.”

Nurses again answered the call with the yellow fever epidemic of 1878, rushing from all over the country to Tennessee. The epidemic ultimately killed 18,000 people, and many nurses died while caring for the sick.

The U.S. recruited more than 22,000 trained nurses to treat Americans overseas and back at home from 1917 to 1919 during World War I. The war brought death from combat to about 53,000 Americans, while about 40 million civilians and military died worldwide. Time after time, nurses have left the warmth, comfort and safety of their homes to care for others.

Nurses were also among the millions who died from the 1918 influenza pandemic. Fifty million people died worldwide. This pandemic is probably most comparable to what we are experiencing today with COVID-19. But epidemics, such as polio, off and on from 1916 to 1954; the global pandemic of influenza A, 1957-1958; swine flu, 2009-2010; Ebola, 2014-2016; and Zika, 2015-2020, have also required constant nursing care.

I remember the AIDS pandemic, which began in 1981. I was a visiting nurse and saw many patients in their homes, from homeless shelters to penthouse apartments. Everyone suffered not only because of the physical and mental effects of the disease but also because of the stigma. People, even their families, were afraid to touch patients, kiss them or be near them. It was a lonely time for these patients. I watched them deteriorate and die. Nurses were often the only ones to hold the hands of these patients, so they wouldn’t die alone.

Nurses were also there during 9/11. They were among the courageous first responders who risked their lives to save others. Many have chronic diseases because of their exposure to Ground Zero.

Every year, nurses are voted first among the professions the public trusts the most, according to Gallup. We work hard to earn and maintain that trust. You will find us caring for people in their homes, in public health departments, in nursing homes and skilled care facilities, in rehabilitation hospitals, in prisons and correctional institutions, caring for the mentally ill and providing health care advice over phones and computers. Nurses work wherever there are people.

What do we ask in return? It’s simple. We don’t consider ourselves heroes, but we do deserve respect. Public images of the nurse in a sexy uniform or as a handmaiden to a doctor are wrong and insulting. We are professionals. Once the COVID-19 crisis is over, please don’t forget that we are always here for you. Always have been. Always will be.![]()

Leslie Neal-Boylan, Dean of the Solomont School of Nursing, University of Massachusetts Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.