Often, you can tell where someone grew up by the way they speak.

For example, if someone in the United States doesn’t pronounce the final “r” at the end of “car,” you might think they are from the Boston area, based on sometimes exaggerated stereotypes about American accents and dialects, such as “Pahk the cahr in Hahvahd Yahd.”

Linguists go deeper than the stereotypes, though. They’ve used large-scale surveys to map out many features of dialects. The more you know about how a person pronounces certain words, the more likely you’ll be able to pinpoint where they are from. For instance, linguists know that dropping the “r” sounds at the end of words is actually common in many English dialects; they can map in space and time how r-dropping is widespread in the London area and has become increasingly common in England over the years.

In a recent study, we applied this concept to a different question: the formation of Creole languages. As a linguist and a biologist who studies cultural evolution, we wanted to see how much information we could glean from a snapshot of how a language exists at one moment in time. Working with linguist Hubert Devonish and psychologist Ewart Thomas, could we figure out the language “ingredients” that went into a Creole language, and where these “ingredients” originally came from?

Mixing languages to make a Creole

When a Creole language forms, it’s generally because two or more populations come together without a common language to speak. Across history, this was often in the context of colonialism, indentured servitude and slavery. For example, in the U.S., Louisiana Creole was formed by speakers of French and several African languages in the French slave colony of Louisiana. As people mix, a new language forms, and often the origins of individual words can be traced back to one of the source languages.

Our idea was that, if specific dialects were common among the migrants, the way they pronounce words might influence the pronunciations in the new Creole language. In other words, if English-derived words in a Creole exhibit r-dropping, we might hypothesize that the English speakers present when the Creole formed also dropped their r’s.

Following this logic, we examined the pronunciation of Sranan, an English-based Creole still spoken in Suriname. We wanted to see if we could use language clues to identify where in England the original settlers came from. Sranan developed around the mid-17th century, due to contact between speakers of English dialects from England, migrants from elsewhere in Europe (such as Portugal and the Netherlands) and enslaved Africans who spoke a variety of West African languages.

As is the case with most English-based Creoles, the majority of the lexicon is English. Unlike most English Creoles, though, Sranan represents a linguistic fossil of the early colonial English that went into its development. In 1667, soon after Sranan was formed, the English ceded Suriname to the Dutch, and most English speakers moved elsewhere. So the indentured servants and other migrants from England had a brief but strong influence on Sranan.

Using historical records to check our work

We asked whether we could use features of Sranan to hypothesize where the English settlers originated and then corroborate these hypotheses via historical records.

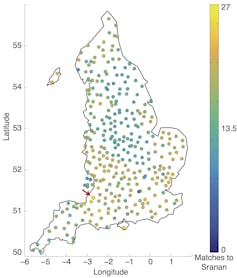

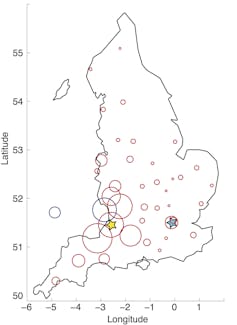

First, we compared a set of linguistic features of modern-day Sranan with those of English as spoken in 313 localities across England. We focused on things like the production of “r” sounds after vowels and “h” sounds at the start of words. Since some aspects of English dialects have changed over the last few centuries, we also consulted historical accounts of both English and Sranan.

It turned out that 80 percent of the English features in Sranan could be traced back to regional dialectal features from two distinct locations within England: a cluster of locations near the port of Bristol and a cluster near Essex, in eastern England.

Then, we examined archival records such as the Bristol Register of Servants to Foreign Plantations to see if the language clues we’d identified were backed up by historical evidence of migration. Indeed, these boat records indicate that indentured servants departing for English colonies were predominantly from the regions identified by our language analysis.

Our research was proof of concept that we could use modern information to learn more about the linguistic features that went into the formation of a Creole language. We can gain confidence in our conclusions because the historical record backed them up. Language can be a solid clue about the origins and history of human migrations.

We hope to use a similar approach to examine the African languages that have influenced Creole languages, since much less is known about the origins of enslaved people than the European indentured servants. Analyses like these might help us retrace aspects of forced migrations via the slave trade and paint a more complete linguistic picture of Creole formations.![]()

Nicole Creanza, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences, Vanderbilt University and André Ché Sherriah, Postdoctoral Associate in Linguistics, University of the West Indies, Mona Campus

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.