Since her mother died last year, 74-year-old Lim Yeo Hong has been living alone in a flat on the outskirts of Singapore, scavenging for cardboard scraps which she sells for a living.

The only time she meets anyone is once a month when she collects food from a charity.

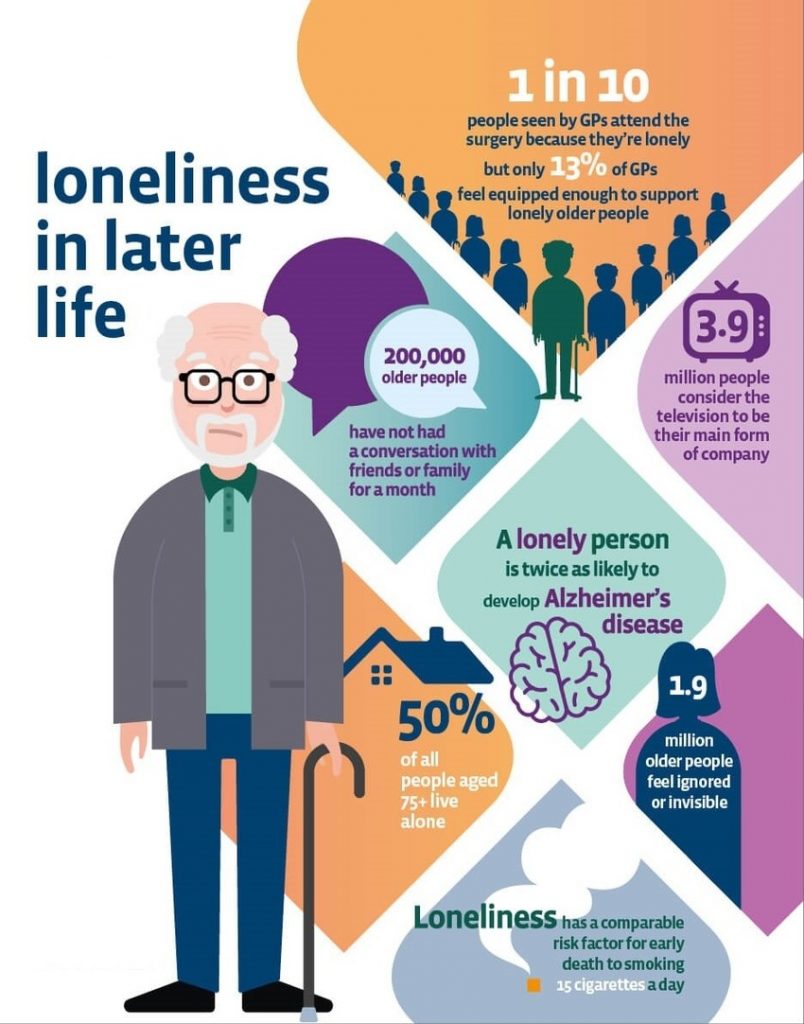

“There’s nothing else I can do at home, I watch TV,” the frail woman told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, taking a break from pushing her cart full of cardboard around an industrial estate on the 5.6 million-strong island nation.

Asked if she felt lonely, she said, “Yes of course I do, but what choice do I have?”

In a rapidly ageing and urbanising world, Lim is among a growing number of elderly people who are grappling with loneliness, which research has linked to poor mental health, including dementia and early mortality.

As people live longer, the World Health Organization predicts that one in five – 2 billion people – will be aged 60 or older by 2050, double that of 2015.

Singapore, the world’s second-fastest ageing society after South Korea, according to the United Nations (U.N.), is being seen as a test-bed on how to help greying citizens live well.

It has hit on the idea of getting more elderly people out of the house and into gardens to reduce time spent alone, as the number of suicides by those aged 60 and above hit a high of 129 in 2017, according to the charity Samaritans of Singapore (SOS).

Mental health disorders are on the rise worldwide and could cost the global economy up to $16 trillion between 2010 and 2030, causing lasting harm to people and communities, according to The Lancet medical journal.

Better urban design and friendlier public spaces could rekindle a sense of community and boost mental health, town planners say, as the U.N. projects more than two-thirds of the world will live in cities by 2050.

New friends

Elderly suicides in Singapore have been driven by a lack of social connection and a growing fear of being a burden on one’s family, said the SOS, a leading suicide prevention group.

“It’s not good coming together and becoming denser … if that density doesn’t allow you to be more social and to have meaningful bonds,” said architect Itai Palti, based in Britain where the government says loneliness is a major health issue.

Urban planners need to rethink how they design cities by making mental and social wellbeing a priority, said Palti, who founded The Centre for Conscious Design, a think-tank.

“We’ve built so much of the world around us with very little consideration of how it has affected us,” he added.

Since 2017, Singapore has rolled out an allotment garden scheme – a shared plot of land where people can farm – which it hopes will foster a love of gardening and closer social bonds.

It has proven popular. More than 1,000 allotment gardens have been leased out to residents at S$57 ($41) annually in national parks across the island, which is dominated by densely packed high rises.

Retired taxi driver Roger Loh said he has been spending at least an hour every day at his allotment, tending to his papaya, chilli and spinach plants.

His wife passed away four years ago. Although he lives with his son and daughter-in-law, they are out working during the day, leaving Loh at home with the dog.

“A lot of old friends are gone already. I need to add some new friends, so here is very good,” said the 78-year-old.

“We talk and we exchange food,” he laughed.

Therapeutic

Another project, known as the “therapeutic” gardens, uses fragrant plants and herbs to stimulate the senses in areas near nursing homes, in a bid to reduce conditions associated with ageing such as dementia and Alzheimer’s.

One in four Singaporeans will be above 65 years old by 2030, double that of 2016, the government estimates.

Such communal spaces help to rekindle the spirit of the “kampung”, a Malay word referring to close-knit traditional villages, said Kay Pungkothai, head of community gardening at the government’s National Parks Board.

“When people come together and grow things, the passion of greening brings out a spirit of togetherness,” said Pungkothai.

“This is what we call a modern ‘kampung’ where people come together, they have a communal space they can go to and look forward to coming to … It really tackles the issue of isolation and depression.”

City dwellers are 21% more likely to develop anxiety, and 39% more likely to have a mood disorder like depression than countryfolk, according to the Arkin Institute for Mental Health in Amsterdam.

Singapore also plans to raise its retirement age from the current 62 and offer incentives to companies which retain older workers to give elderly people a sense of purpose, income and social connections.

Nafiz Kamarudin, who since 2013 has run a charity helping elderly people, said spending time with a group is as important as welfare programmes.

His charity Happy People Helping People Community hands out food aid to poor senior citizens – like 74-year-old Lim – and organises a monthly gathering where they can mingle.

“They just want something to look forward to every month rather than every day being like a repeat of the previous day,” said Nafiz.

This article is republished from World Economic Forum.