We would like to thank our generous sponsors for making this article possible.

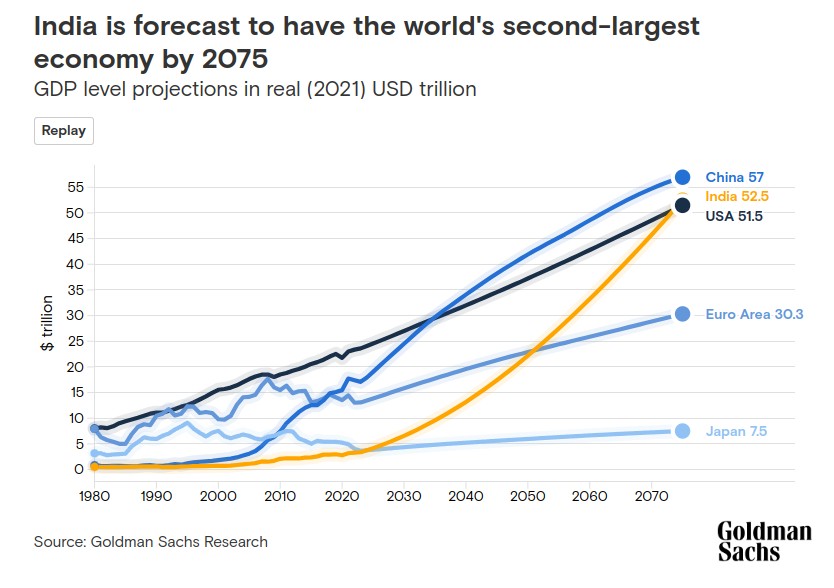

As India’s population of 1.4 billion people becomes the world’s largest, its GDP is forecast to expand dramatically. Goldman Sachs Research projects India will have the world’s second-largest economy by 2075.

For India, a key to realizing the potential of that growing population is boosting participation within its labor force, as well as providing training and skills for its immense pool of talent, says Santanu Sengupta, Goldman Sachs Research’s India economist. “Over the next two decades, the dependency ratio of India will be one of the lowest among regional economies”, he says, pointing out that India’s population has one of the best ratios between its working-age population and its number of children and elderly. “So that really is the window for India to get it right in terms of setting up manufacturing capacity, continuing to grow services, continuing the growth of infrastructure.”

We spoke with Sengupta about the underpinnings of India’s economy, the demographic factors driving GDP forward, and the country’s ambitions for green energy.

What are the main drivers of Goldman Sachs Research’s long-term forecasts for India’s economy?

India has made more progress in innovation and technology than some may realize. Yes, the country has demographics on its side, but that’s not going to be the only driver of GDP. Innovation and increasing worker productivity are going to be important for the world’s fifth-biggest economy. In technical terms, that means greater output for each unit of labor and capital in India’s economy.

Capital investment is also going to be a significant driver of growth going forward. Driven by favorable demographics, India’s savings rate is likely to increase with falling dependency ratios, rising incomes, and deeper financial sector development, which is likely to make the pool of capital available to drive further investment.

On this front, the government has done the heavy-lifting in the recent past. But given healthy balance sheets of private corporates and banks in India, we believe that the conditions are conducive for a private sector capex cycle.

Finally, favourable demographics will add to potential growth over the forecast horizon. India’s large population is clearly an opportunity, however the challenge is productively using the labor force, by increasing the labor force participation rate. That will mean creating the opportunities for this labor force to get absorbed and simultaneously training and upskilling the labor force.

How do India’s demographics compare to other large countries in terms of aging and fertility?

In India, the demographic transition is happening more gradually and over a longer time period than the rest of Asia. This is primarily due to a more gradual decline in death and birth rates in India compared with the rest of Asia.

The population growth will continue. What we focus on is the dependency ratio, which is the non-working-age population that is dependent on the working-age population. For India, that will be among the lowest among large economies for the next 20 years or so. So that really is the window for India to get it right in terms of setting up manufacturing capacity, continuing to grow services, continuing the growth of infrastructure.

There’s a lot of infrastructure creation that is going on now, primarily led by the government’s focus on setting up infrastructure in terms of roads, railways and so forth. We believe this is also the appropriate time for the private sector to scale up on creating capacities in both manufacturing and services which has the potential of creating jobs and absorbing the large labor force.

What are some of the risks to Goldman Sachs Research’s forecasts for India’s economic growth?

The main downside risk would be if the labor force participation rate does not increase. The labor force participation rate in India has declined over the last 15 years. If you have more opportunities — especially for women, because the women’s labor force participation rate is significantly lower than men’s — you can shore up your labor force participation rate, which can further increase your potential growth.

Growth upside can come through higher productivity growth. India has taken a giant leap in terms of digitalization of the economy, both through wider penetration of Internet and mobile Internet. But along with that you’ve had the unique identification number, or what is called the Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric ID system, by which you are now able to verify identification of the 1.4 billion population both online and physically. So it makes public service delivery much easier and more targeted. It widens the credit net, leads to smaller businesses getting more credit, and that can provide an upside to growth from an increase in productivity.

What are some of the other key factors to understanding India’s economy?

It’s a very domestic-demand-driven economy compared to many others, especially in the region which are more export dependent. India’s growth until now has been mainly driven by domestic consumption as the main driver, around 55-60% of the overall economy, plus domestic investments.

Net exports have always been a drag on growth, because India runs a current account deficit. In recent times, we are seeing some progress on that front. Services exports have been increasing, and that is somewhat cushioning current account balances.

The other important factor to keep in mind is how commodity prices affect the macro economy — inflation, fiscal deficit, and current-account deficit. India imports most of the commodities that are required for a large population. And when commodity prices globally go up it obviously shows up in macro imbalances.

Over the last few years, those macro imbalances are reducing, and you’re getting less macro vulnerability from, one, inflation targeting and, two, through services exports, which is cushioning the current account balance.

And which commodities are particularly noteworthy for India’s current account?

A large population has its energy requirements. Although the per-capita consumption of energy is way lower than not just the Western world, but also other emerging economies, the large population means a large energy import bill and shows up in India’s current account imbalances.

This was more true around 10 years back. Over the last five years or so, there is growing resilience in the external balance dynamics through a structural improvement in current accounts through services exports and due to the central bank consciously building reserve buffers, which gives more cushion during episodes of dollar strength.

Is green energy and the energy transition an opportunity for India?

Absolutely. India has announced that it aims to reach net zero emissions by 2070 and for 50% of the power generation capacity to come from non-fossil sources by 2030. The government is also pushing EVs and green hydrogen, and is targeting 500GW of renewable or clean energy capacity by 2030.

Ultimately, transitioning to green energy is a large investment opportunity, but it’ll take time. In the interim fossil fuels are going to be the majority share in energy needs until India transitions to green energy.

This article is being provided for educational purposes only. The information contained in this article does not constitute a recommendation from any Goldman Sachs entity to the recipient, and Goldman Sachs is not providing any financial, economic, legal, investment, accounting, or tax advice through this article or to its recipient. Neither Goldman Sachs nor any of its affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the statements or any information contained in this article and any liability therefore (including in respect of direct, indirect, or consequential loss or damage) is expressly disclaimed.

Originally published at: Goldman Sachs