New York City’s experience as the epicenter of the U.S. COVID-19 outbreak is raising questions about urban living. Quarantined residents worry about the future in a city known for its tight quarters and full theaters.

But cities have long had to transform themselves to overcome disease.

My research on urban planning and infectious disease traces this pattern to the founding of the nation.

Yellow fever and cholera

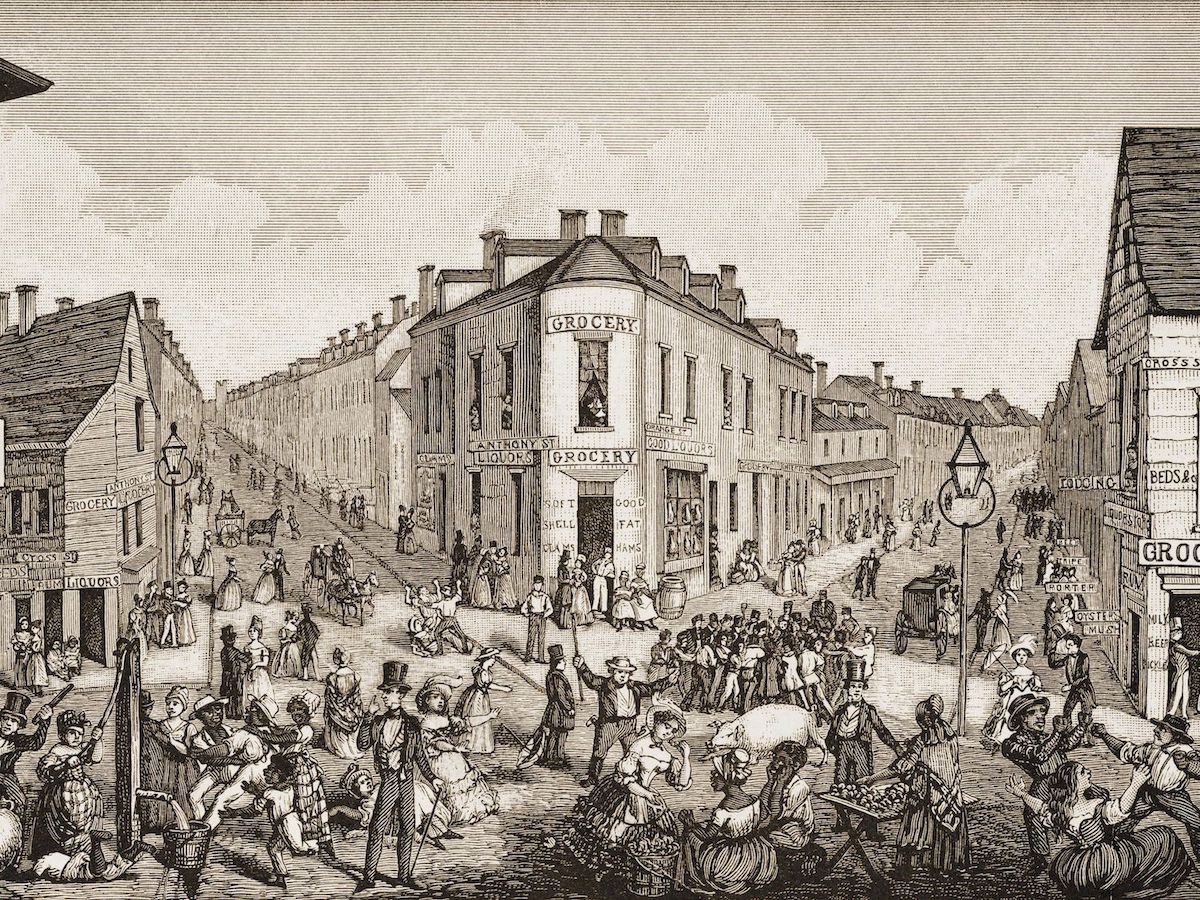

In 1793, a yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia killed 5,000 people – about 10% of what was then the U.S. capital’s population. At the time Philadelphia, like all American cities, had no municipal garbage services. Hogs roamed streets and ate garbage.

On the advice of prominent doctors who redirected blame for the outbreak away from immigrant communities toward sanitizing the city – presciently, since germ theory had not yet been invented – Philadelphia’s mayor authorized emergency funding to treat the sick and clean the gutters.

Such efforts were a harbinger of urban planning reforms, as cities would take on the costly job of garbage removal and create sanitation departments over the next 50 years. These measures greatly improved residents’ health in the short and long term. They also added alleyways to cities, for garbage removal.

When contaminated water brought waves of cholera sweeping through the U.S. in the 1850s, cities across the country birthed the twin agencies of public health and urban planning to make and enforce regulations. In the same period, New York City’s Board of Health made way for Central Park – the nation’s first public park – on the premise that open urban space improved human and environmental health.

The park housed a reservoir designed to deliver fresh, clean water to the burgeoning city. It received water from one of the nation’s first great aqueducts.

For the first time New York’s housing development was planned, with growth attached to funding for sewer and water lines. By 1916, this patchwork of development directives was compiled into the U.S.‘s first citywide zoning code.

Cities everywhere followed New York’s example, taking control of land use and vanquishing waterborne pathogens like cholera and polio by the mid-1900s.

Battling airborne pathogens

Airborne illnesses, which make up eight of the 10 most recent pandemics, however, are proving difficult to combat.

When Egypt faced H1N1 swine flu in 2009, officials in Cairo misdiagnosed the problem, focused on slum clearance and culling pigs instead of breaking human-to-human transmission. Swine flu, an airborne illness, contains pig genes but cannot be transmitted by pigs.

Since many Cairo neighborhoods rely on a Coptic Christian group called the Zabaleen to remove waste – which they later feed to pigs – the streets soon filled with garbage. Rat populations boomed. Typhoid, cholera and other diseases resurged.

Breaking airborne disease transmission requires reducing human-to-human contact through physical distancing and business closures, for example, and wearing masks to impede infectious droplets. Shelter-in-place orders, like those in place in all but eight U.S. states, prevent travel-related disease spread.

Because lockdowns are difficult to maintain over time, policymakers are searching for longer-term solutions.

“NYC must develop an immediate plan to reduce density,” tweeted New York Governor Andrew Cuomo on March 22, reviving a longstanding argument that density contributes to greater human-to-human contact and illness.

Yet while dense major cities are more likely entry points for disease, history shows suburbs and rural areas fare worse during airborne pandemics – and after.

According to the Princeton evolutionary biologist Andrew Dobson, when there are fewer potential hosts – that is, people – the deadliest strains of a pathogen have better chances of being passed on.

This “selection pressure” theory explains partly why rural villages were hardest hit during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Per capita, more people died of Spanish flu in Alaska than anywhere else in the country.

Lower-density areas may also suffer more during pandemics because they have fewer, smaller and less well-equipped hospitals. And because they are not as economically resilient as large cities, post-crisis economic recovery takes longer.

Unpaving the way

Common-sense steps cities can take to fight the coronavirus are emerging.

One promising pilot involves closing some streets to cars, as Oakland and New York, among others, have done. This allows city dwellers to get outside and walk – but not too close together – as recommended for maintaining physical and mental health.

Such pilot closures may eventually “unpave the way,” creating urban greenbelts for walking and biking at a safe distance in even the densest of places. Easy access to nature has additional benefits for urban areas, among them keeping productive farmland and a fresh food supply nearby.

Another coronavirus initiative focuses on protecting the most exposed city residents.

Anti-poverty centers, city agencies launched after the 2008 Great Recession, are now focused on anti-eviction legislation and rent control measures to prevent homelessness during the pandemic. Keeping people safely inside helps to stop the spread of this virus and will likely reap public health dividends beyond the pandemic.

For centuries diseases have forced American cities to make such changes – to innovate in ways that ended up benefiting all future residents.

Pandemic-related urban policy advances like ceding more terrain to pedestrians or structurally addressing homelessness take time to emerge. My research identifies some reflexive denial early in an outbreak.

But, ultimately, American cities have triumphed over infectious diseases many times before. I’m hopeful we can do it again.

![]()

Catherine Brinkley, Assistant Professor of Community and Regional Development, University of California, Davis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.