Osmel Martinez Azcue felt unwell. Having recently returned home to Florida from China and experiencing flu-like symptoms, he went to his local hospital to get tested for coronavirus. While the test was negative, Azcue has since been billed for $3,000 – he’ll be responsible for $1,400, according to his insurer.

While there’s been no charge for Center for Disease Control-led coronavirus testing in public health labs in the US, the additional and related costs incurred by patients such as Azcue, from transport to tests for other flu strains, remain. As Azcue’s bill shows, that’s expensive with insurance; for the estimated 27.5 million in the US – 8.5% of the population – who went without healthcare in 2018, the individual cost of dealing with this pandemic could be devastating.

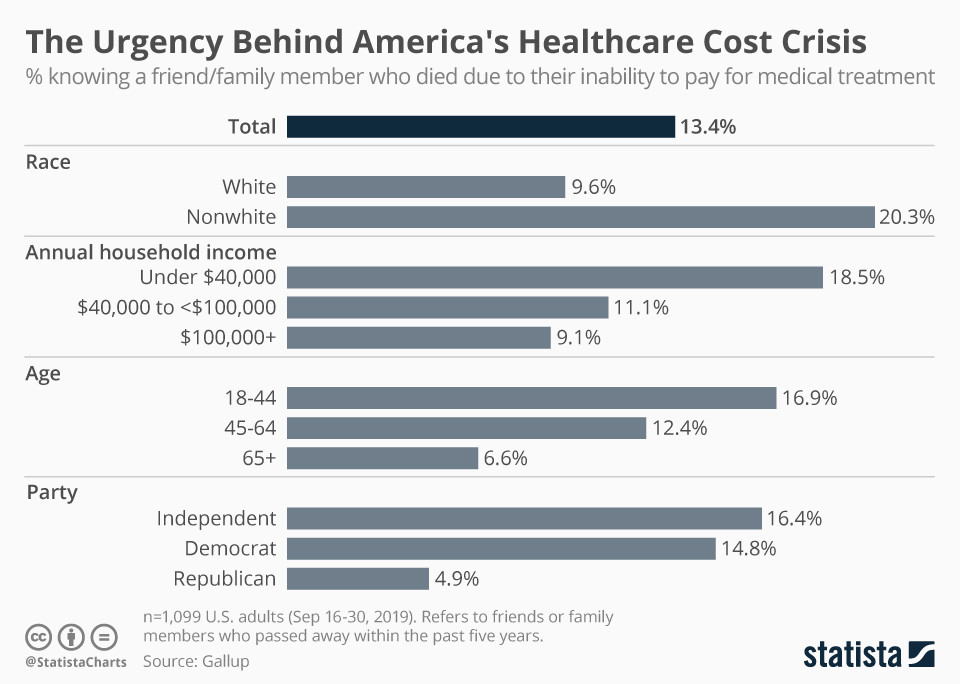

The coronavirus outbreak is a stark reminder of the divide that exists in countries without universal healthcare, like the US, between those who can afford healthcare and those who cannot and may be forced into extreme poverty as a result.

In the US, concerns have also been raised about access to any future coronavirus vaccine after the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, said he could not guarantee it would be affordable to all when available.

On 12 March, Africa registered its first coronavirus death. The number of cases in the continent has “mushroomed in the last week” according to the BBC and concerns are growing for populations in Africa – and the world’s – poorest countries where health systems are weaker.

“Our biggest fear involves cases arising in poor, densely populated neighbourhoods,” Dr Michel Yao, Emergency Operations Programme Manager at the WHO’s Regional Office in Africa, told The Africa Report.

“In this type of situation, if health facilities don’t have the appropriate capacity to treat patients, then the death toll could be significant. And what makes this even more crucial is that the coronavirus could decrease our resources for treating other diseases such as malaria and for ensuring maternity and child healthcare.”

Access to healthcare and the capacity of health systems will be a heightened concern at this time for those already living in poverty or experiencing income inequality, especially as the pandemic brings additional economic risks for low-income or less secure workers.

While companies such as Twitter, Facebook and Google have instructed many staff to work remotely or from home, for millions of workers around the world this is not an option.

“If we don’t work, we don’t get paid,” Fina Kao, a worker in a donut shop in San Francisco, told Time. For Kao and others whose jobs rely on contact with other people, for the 49% of the world’s employed population working in the service industry, the fear of exposure to the virus is real but so is the fear of losing hours or much-needed pay.

“In this way, the spread of the coronavirus exposes a widening chasm in the US economy between college-educated workers, whose jobs can be done from anywhere on a computer, and less-educated workers who increasingly find themselves in jobs that require human contact,” writes Alana Semuels.

Gig economy workers, such as Deliveroo riders or Uber drivers, and the self-employed are not entitled to statutory sick pay. They may, however, be the ones delivering essentials to increasingly self-isolating populations, putting their own health at risk for low reward.

“If I catch something I’m screwed,” 23-year-old Shane Stephen, a Deliveroo courier told the Guardian. “Gig economy workers can’t afford to be ill. My bank balance is literally £4 something right now.”

In the US, Lyft has said it will “provide funds to drivers diagnosed with COVID-19 or placed under quarantine”, according to the Los Angeles Times. In the UK, one of the largest delivery firms with 15,000 couriers, Hermes, has confirmed it will pay self-employed couriers if they are told to self-isolate because of coronavirus. The UK government, however, has not yet extended changes to statutory sick pay for workers to cover the self-employed.

The number of people working in-person jobs with low pay is growing rapidly in the US. These include restaurant and retail staff and food preparation jobs – roles for businesses that rely on people and customers leaving their homes and spending. The coronavirus pandemic is likely to hit these businesses hard; the reality for their low-income employees could be even worse.

Source: World Economic Forum