With the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China, stories of courage and strength have captured our collective attention as the disease spreads.

We have also seen large-scale efforts in China to combat coronavirus, including the construction of new hospitals and facilities in provincial areas as well as the massive quarantine of millions of people.

While efforts to address the disease move forward, the outbreak has also revealed the darker side of human nature and our responses to new diseases and other catastrophic events: mistrust, fear and outright racism.

Here in Canada, we have seen racism and stereotyping of the Chinese community as the number and location of cases of coronavirus have spread and fear of the outbreak festers.

The surge of fear and racism in the face of this latest outbreak is similar to previous experiences in the wake of other diseases, such as the Ebola and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) viruses.

Yet the prevalence of racism and scapegoating in the face of catastrophes and disasters has a much longer history than these more recent outbreaks.

This history provides important context and is worth reflecting upon. It reminds us that disasters and catastrophes are not exclusively natural phenomena, and are also a result of the economic, political and social decisions that create vulnerability to risk.

Importantly, discrimination, racism and scapegoating has been used to distract from the underlying economic, political and social decisions that produced vulnerability to disaster and disease in the first place.

Disasters aren’t natural

While many headlines highlight “natural” disasters in the aftermath of the latest catastrophe, researchers in the field of disaster studies have long demonstrated the social construction of these events.

This means that catastrophes, whether they’re the latest earthquake, hurricane or outbreak of disease like the coronavirus, are fundamentally connected to underlying factors that affect which areas and individuals are vulnerable and why.

Given these links, we must understand that there are specific interests, usually associated with the exercise of power, involved in how we view these connections or how we’re distracted from them.

In the case of the coronavirus, the recent death of Dr. Li Wenliang, who was censured by police over his early warnings about the disease, is an example of how power operates. He was reprimanded and silenced by the police in Wuhan and was forced to sign a letter saying he had made “false comments.”

It reminds us that accepting the relationship between economics, politics and the production of risk and vulnerability means that catastrophic events aren’t just natural phenomena — they are also political phenomena.

Tied into this political nature, disasters often result in people placing blame upon certain communities and groups for the event in question. This scapegoating diverts attention away from the underlying causes connected to economic, political and social decisions as well as the exercise of power.

Ebola fears

A similar epidemic of fear followed the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, which resulted in the racist targeting of certain individuals and communities as the crisis worsened.

This discrimination suggested there was no understanding of the Ebola outbreak within the larger history of the region.

Powerful global players, including the United States, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, pushed various West African governments to adopt Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) to reduce deficits and make those states more attractive to investors and the global capital markets.

In order to achieve this, SAPs required spending cuts to the health-care systems of those states, ultimately increasing the vulnerability of those populations to outbreaks of diseases like Ebola.

As with the current outbreak of 2019-nCoV in China, scapegoating and racist fearmongering pointed the finger of blame at the Ebola victims themselves, not the underlying factors and decisions by the powerful that contributed to the crisis.

The racism seen in the case of 2019-nCoV is just the latest example of how power is used to politicize and manipulate disasters.

Long history

Scapegoating, discrimination and victim-blaming have been prevalent in the aftermath of other catastrophic events.

They are also related to religious or spiritual understandings of disasters and disease as divine retribution or punishment.

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 resulted in various versions of this phenomenon. Many prominent conservative Christians blamed the hurricane on the LGBTQ+ community and the city’s “sinful” reputation.

The narratives surrounding Hurricane Katrina also reinforced racist stereotypes and tropes through media coverage on survivors based on their race: Black survivors were routinely characterized as “looting” in the aftermath of the storm, while white survivors were described as “finding supplies.”

This harmful and false narrative was hardly unprecedented.

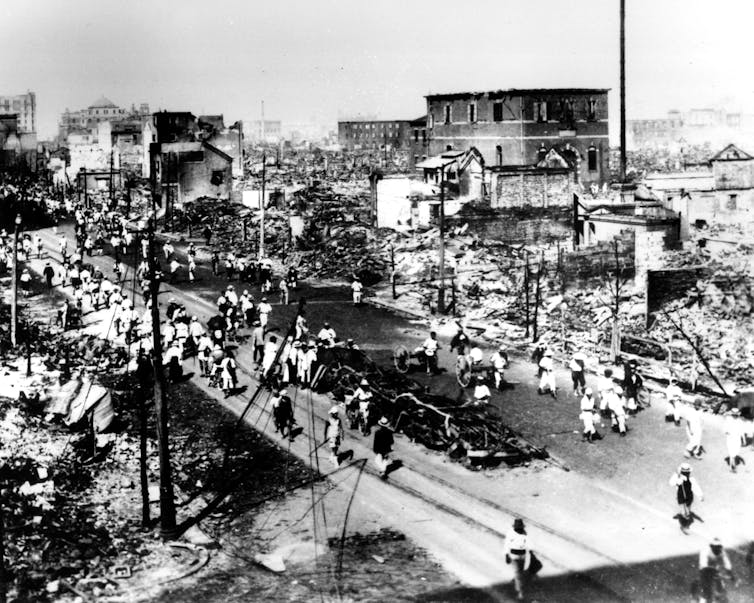

Going back even further, the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 led to racist pogroms, or massacres, against some 6,000 Koreans living in Japan due to rumours that they were setting fires that spread in the aftermath of the quake.

These Japanese-Korean tensions flared up decades later, in 2017, when Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike refused to send the annual eulogy for victims of the pogroms, suggesting there was doubt that the massacres occurred.

Koike’s decision demonstrates how disasters and discrimination are tethered to the operation of power and control over how these events are understood, even a century later.

Disasters clearly foment discrimination. And so we should expect these types of responses to future catastrophes and take proactive steps to address them.

Furthermore, we need to be mindful of how certain narratives and understandings of disasters act to distract us from far more important elements — including those that leave all of us vulnerable to disasters and disease.![]()

Korey Pasch, PhD Candidate in Political Science and International Relations, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.