These days every hour we are inundated by data and information so much so the World Health Organization (WHO) coined a word for it “infodemic.” It is defined as “an overabundance of information – some accurate and some not – that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it.”

Yet health data confusion and its manipulation are not new, infodemic is merely the latest manifestation, with a direct reference to the pandemic. For instance, up until the 1960s, the tobacco industry in the United States was hugely successful in smoking over the health consequences of tobacco products. The leading manufacturers had had overwhelming evidence that cigarettes cause cancer and lung disease with harmful effects for many years. Their strategy was to promulgate expert disagreement and doubt to smokers and to give cover for future young smokers who might do so for social and peer group reasons.

Darrell Huff, the author of “How to Lie With Statistics”, a seminal work showing aspects of statistical trickery, later became a flack for the tobacco industry. He appeared at a U.S. Senate hearing looking into the need for health warnings on cigarette packaging and advertising, countering the need for such labeling by citing a statistical correlation between babies and storks, paralleling the connection between smoking and cancer as equally unsupportable.

Today, COVID-19 dominates virtually every media.

The preponderance of COVID-19 data sources support policies that promote social distancing, lockdowns, masks, and face shields to contain the virus; other sources contradict, with claims of no value or that such use is negative in preventing herd immunity progress. And this is where the COVID infodemic comes in.

We, the public, are confounded and confused by the vast amount of expert pronouncements thrown at us from multiple sources which supposedly shed light on how to protect our health, or what to do when we are infected with the virus. This mudding of the perception waters has been done extensibility and excessively by both the private and public sectors alike.

Let us look at a few of the major information challenges and sources.

How many people have been infected or died from the disease? A reporting infodemic

The internet and major news outlets provide numbers that vary widely—sometimes by thousands of cases. Some morbidity and mortality sources factor in only confirmed cases, some eliminate those with a contributing factor, while others include “presumptive cases,” patients who tested positive by a local public or private health laboratory but whose results are still pending confirmation.

A reasonably reliable source is the WHO which provides global numbers of confirmed COVID-19 infections and deaths, as well as information on the totals for parts of the globe that are hardest hit.

Different media outlets and institutions provide charts, dashboards, maps, and infographics to update and explain the virus, including colorful, real-time versions. These presentations can be accurate or inaccurate.

The source of the information is just the starting point, namely does the public governmental or non-governmental institution, university, research institute have a reputation for, and stake in, providing evidence-based data.

Initially, there were only a few data points to consider, namely those from the People’s Republic of China in terms of the number of positive COVID cases and deaths. Subsequently, the worldwide epidemiology community sprang into action to get a better handle on the extent to which this virus represents a serious public health threat.

Johns Hopkins University created its dashboard of data resources; the Atlantic magazine launched its COVID Tracking Project; and as mentioned, the World Health Organization global platform.

These sites have been largely dependable but even they require a word of caution: Some, at times, have been successfully attacked by malware to both distort the information site and misappropriate user information.

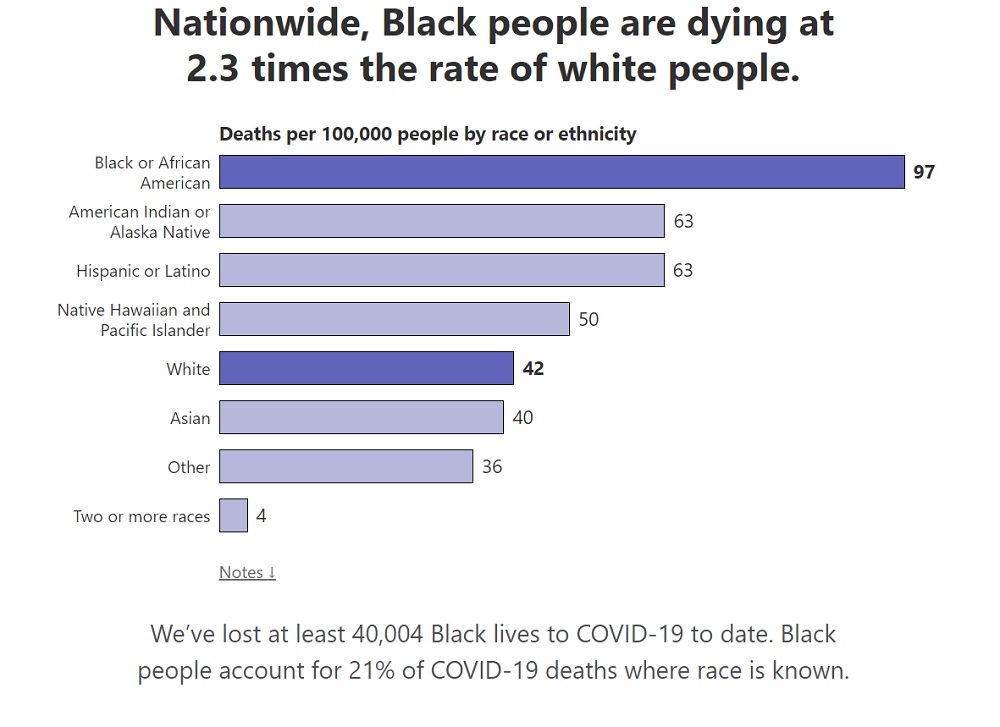

Beyond those named, many other sources have emerged, adding statistics well beyond basic morbidity and mortality figures to disaggregate location, ethnicity, age cohort, and income. Nature magazine has characterized this information explosion as “a coronavirus data crisis,” one in which “political meddling, disorganization and years of neglect of public health data management mean the country (and not just the United States) is flying blind.”

Where are we in basic understanding of the virus and promising research to help us?

Basic science studies and clinical trials have a powerful way of generating headlines, but the devil is in the details which are usually “below the fold” in newspapers.

In fact, it will take years before we have enough evidence from research to get the full picture of COVID-19. While we are learning more with each passing day, we are far from having adequate data from randomized trials. For example, we don’t know the extent of aerosol delivery, whether and how much asymptomatic people unknowingly spread the virus, the extent of post-recovery damage for young, old, and those with existing conditions, as well as whether there are differences in transmission in Asia, Africa, Europe, the Americas.

Separating fact from fiction is especially difficult when the source is social media. The credibility of the source is crucial: A tweet from Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has greater reliability than a tweet that says the opposite from a movie star, an unknown, or possibly faux scientist.

WHO has been working with social media channels to ensure that when someone searches the internet for “coronavirus” or “COVID-19,” or a related term, a box comes up directing them to WHO’s “Mythbusters”; another such source is the Wikipedia list of unproven COVID methods.

There are numerous trials underway to find therapeutics and a vaccine for COVID-19. While these are worthy and unprecedented global research efforts, incomplete information makes “good news” for increasing readership and viewer numbers and excites the public.

But it is not good for the public.

The Russians, Chinese, United States, other governments, universities, and private companies are racing to get the first COVID-19 vaccine, not only to save humanity but for profit, prestige, or political advantage. Some claim already to have gone through critical testing phases or soon will, to offer their version to those inside their country and outside to friendly allies.

Media is raising expectations that a (or several) safe and effective vaccines will soon be available and widely accessible so life can return to almost normal. This can turn out to be misplaced “news” with unfortunate consequences. Fast-tracking the vaccine development process is complicated: The search for vaccines (as noted in the above video) is a matter of trading off speed and safety and the risks are high as is the likelihood of error and disappointment.

Even with an “approved vaccine,” the anti-mandatory vaccination movement is significant and growing. Well-known figures such as Robert F Kennedy Jr., Robert De Niro, Charlie Sheen, are opposed to mandatory vaccination and this sizable movement can essentially “trump” the desired benefits of vaccines.

If the percentage of people is too small, only those vaccinated will be protected, not their neighbors.

Who might be “providers” of COVID information?

Official country sources may intentionally or unintentionally confuse health professionals and the public about many COVID-19 aspects: Using different definitions for the number of tests given; the reliability in terms of false positives; the length of time from test to notification and access to data collected; reducing the number of COVID-19 deaths when there are contributing factors, or simply withholding data.

Virus information can also be withheld or manipulated for non-scientific reasons, such as “not to cause panic” as the U.S. President said on tape, or when a national leader, in this case, the United States, “downplays” – essentially disregards – scientific leadership and advice, talking and/or behaving to publicly explicitly or implicitly offer an off-ramp for the public and other officials not to wear masks or practice social distancing.

Notably, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), America’s – and even the world’s – foremost center of excellence to battle disease have been under siege from false accusations and interference from the Trump administration. In all, as noted in the Washington Post, the CDC “has lost institutional credibility when we need it the most”.

The political rationale for disregarding scientific advice: This is a form of government intrusion/aggression on personal freedom to be resisted. And many people listen to their political leaders and do resist. In some U.S. jurisdictions, laws requiring masks and social distancing have been passed and resulted in fines and jail because of the unwillingness of some to comply.

While the risk of noncompliance espoused by the U.S. President likely puts more Americans at risk, it also becomes a license for other countries and individuals elsewhere to follow suit. A just-released Cornell University study of 1.1 million stories concluded that “the President of the United States was likely the largest driver of [a] COVID-19 misinformation ‘infodemic.’”

That the President of the United States and his wife were COVID-19 positive and will quarantine as this article comes online, speaks for itself about the dangers of the virus, not wearing masks, social distancing, and other widely acknowledged preventive measures.

Modification of data and information can also come from those claiming to offer straight talk for the “common good.” Charities and non-governmental organizations can have particular issues or support specific vulnerable populations which can lead them to overstate the COVID-19 effect to gain widespread public support and donations.

Then, of course, there are the vast numbers of conspiracy theorists, hoaxers, and scam artists who promulgate preventive and therapeutic falsehoods to convince and profit from the public’s hunger for ways out of our current nightmare.

Last week, all over Europe thousands gathered with many calling the pandemic a hoax. Daniel Jolley, an expert in conspiracy theories, points out that “People are drawn to conspiracy theories in times of crisis,” he said. “When there is something happening — a virus outbreak, rapid political change, the death of a celebrity, a terrorist attack — it breeds conspiracy theories.”

On 23 September, WHO, the UN and partners such as the International Red Cross and Red Crescent called on countries to develop and implement “action plans” to promote the timely dissemination of science-based information and “prevent the spread of false information while respecting freedom of expression.” A timely move but much will depend on how widely it is followed.

In short, in this article, I provide only the tip of the COVID-19 infodemic iceberg. The extent to which the COVID-19 story will reflect responsible reporting, mere “optimism,” falsehoods, or dangerous hyperbole, only we the public, and time will tell. But where we are today is shaped by our preconceptions, emotions, and politics.

Let us hope we get wiser with time.

Republished from Impakter.