We would like to thank our generous sponsors for making this article possible.

After 300 years of hydrocarbons driving the global economy, this century is witnessing the rise of green electric power as a primary source of energy. The shift is being helped along by rising social acceptance of green power, growing policy support, and increasingly attractive economics — most capital expenditures for electrification in Europe are deflationary compared with hydrocarbon alternatives, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

Electrification has the potential to cut European energy bills significantly, writes Alberto Gandolfi, head of the European Utilities Research team in Goldman Sachs Research, in the team’s report. “We model the full electrification of a typical European household and conclude that switching to electric heating and electric mobility would lower the overall energy bill by more than 50%,” he writes.

A European household investing in a new heat pump or electric vehicle could see a payback period as short as three and a half years, Goldman Sachs Research finds. That would help eliminate carbon emissions from households, which are estimated to make up about 30% of the total carbon footprint in the EU and UK.

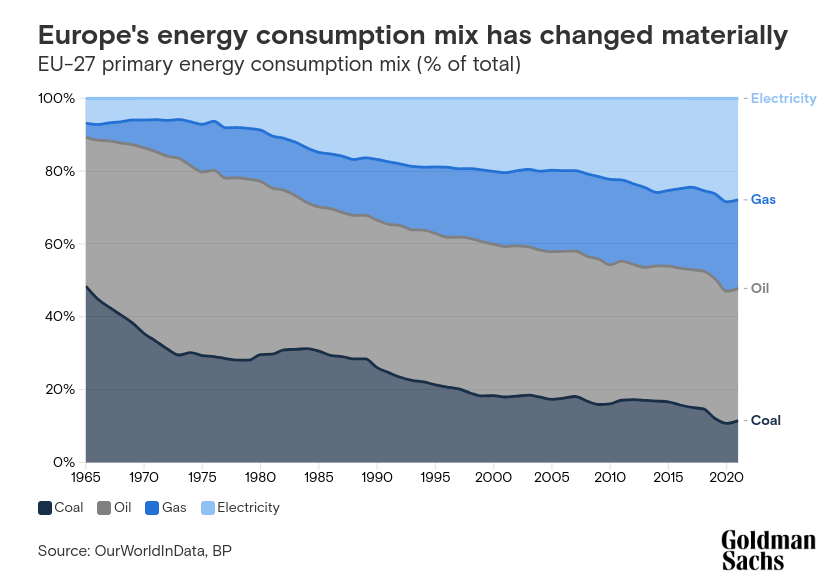

EU planning (known as the REPowerEU plan) indicates electricity could make up 55% of primary energy consumption by 2030, up from about 20% in 2000 and 28% today. The electrification push can help cut carbon emissions and boost energy security, since 80-90% of Europe’s hydrocarbons are imported. Re-industrialization goals might also be supported, if electrification is properly implemented and is deflationary, Gandolfi writes. The UK also has a plan for energy security and reaching its net zero commitments, known as Powering up Britain.

How green energy can change Europe’s economy

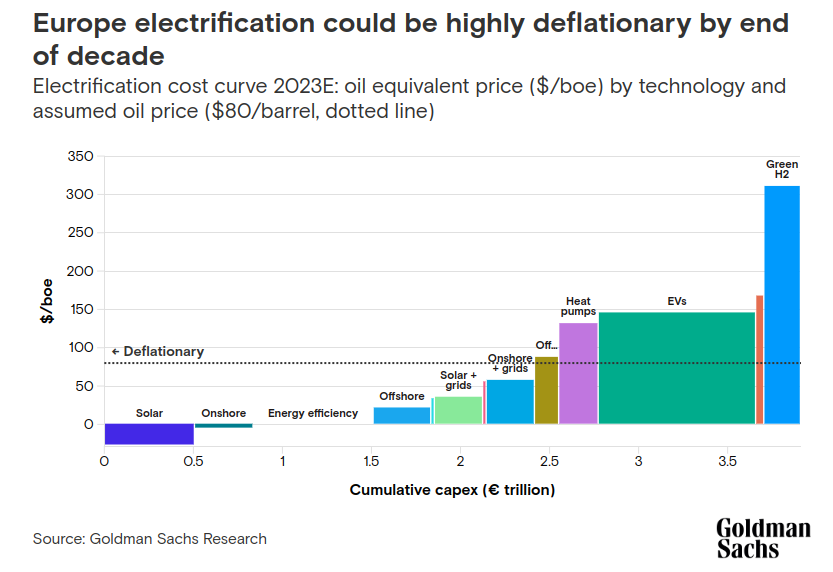

Goldman Sachs Research’s “electrification cost curve” looks at the relative costs of the investments that will be needed for electrification in Europe and in the US. The analysis compares the likes of solar, onshore and offshore wind, power grid improvements, heat pumps, electric vehicles, and hydrogen production — ranking them from least to most expensive.

The analysis shows that more than 70% of the electrification process in Europe over the next 10 years will be deflationary, when using a benchmark of $80 per barrel oil. This calculation is based on the percentage of invested capital going to technologies that feature lower equivalent costs than their hydrocarbon alternatives. By 2030, almost 90% of green capital expenditures in Europe will be deflationary, as the economics improve for electric vehicles, in particular.

Applying the same analysis to the US, “we see that the situation appears very different,” Gandolfi writes. Only about one third of the electrification process would be deflationary over 10 years (at an oil price of $80/barrel or higher). A key difference that affects the numbers for the US economy is, simply, lower energy bills. Fuel is cheaper thanks to shale gas production, and the US lacks carbon levies. Gasoline is also cheaper, which makes EVs less competitive with combustion engines.

Goldman Sachs Research points out that their cost curve for electrification in Europe over the next decade implies that most of the process can happen without meaningful subsidies. “Incentives may be required for the re-shoring of the supply chain, but the roll-out of renewable energy, and the associated incremental costs for power grids and storage, would require almost no green subsidies,” Gandolfi writes.

The smaller portion of green capex that would be deflationary in the US, on the other hand, supports the argument that the $400 billion in electrification incentives contained in 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act are needed “to avoid a near-term impact on consumers,” Gandolfi writes.

How big is the market for green energy?

While opportunities vary across technologies and the different stages in the investment cycle, “electrification is likely to prove a positive secular driver” for stocks tied to the energy transition, Gandolfi writes. The EU’s energy plans and the spending mobilized by the US Inflation Reduction Act suggest an addressable market of more than $6 trillion.

“Our analysis appears highly supportive of rapidly accelerating investments in onshore activities, solar in particular, where increasingly attractive economics could suggest a larger share in the energy mix,” Gandolfi writes. The cost of solar modules has continued its long decline and is near a record low. The report puts the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar at about $45 per megawatt-hour (MWh).

By contrast, the cost of offshore wind power, which declined for 20 years, has reversed direction. Inflation has affected raw material costs for offshore, and funding costs have spiked. The report finds that offshore has become less competitive with other technologies, particularly in the US, where its LCOE is around $135/MWh.

This article is being provided for educational purposes only. The information contained in this article does not constitute a recommendation from any Goldman Sachs entity to the recipient, and Goldman Sachs is not providing any financial, economic, legal, investment, accounting, or tax advice through this article or to its recipient. Neither Goldman Sachs nor any of its affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the statements or any information contained in this article and any liability therefore (including in respect of direct, indirect, or consequential loss or damage) is expressly disclaimed.

Originally published at: Goldman Sachs