Lockdowns across Europe to curb the coronavirus pandemic drastically changed how we move around the world. Work-from-home restrictions, furlough schemes and job losses left millions of cars gathering dust in driveways.

It is not surprising that the demand for new cars plummeted. In Germany – Europe’s largest car market – new car registrations in the first half of 2020 declined by 35% compared to the same period in 2019, and during the height of restrictions (April), sales slumped a historic 61%. Sales for 2020 across the rest of Europe’s largest car markets in the first half of 2020 performed even worse: Spain (-51%), UK (-49%), Italy (-46%) and France (39%).

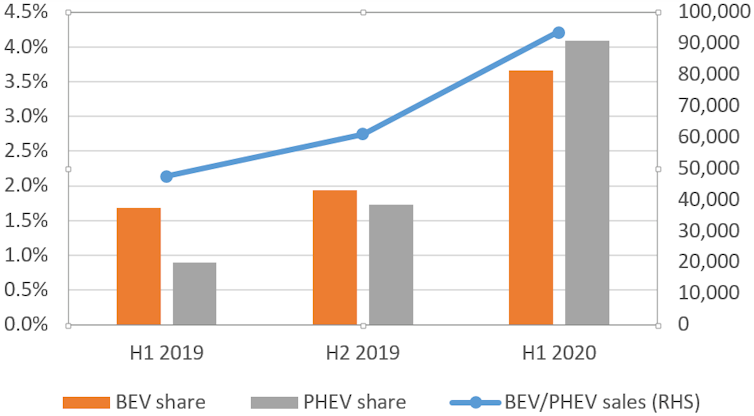

But one segment of the car market is still growing. Electric vehicle (EV) sales, both full battery electric vehicles (BEV) and plug-in-hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) have bucked the trend, not only in terms of their market share, but also in absolute terms. In Germany, EV sales from January to June increased from 47,584 in 2019 to 93,848 in 2020, supported by particularly strong PHEV growth.

This is an incredible performance, given the current economic and public health situation. Similar trends are evident across Europe with France, for example, seeing an even higher shift to EVs in 2020.

Declining car sales

Before we label EVs as the new iPhone, it’s good to take a step back and look at the fundamentals of the struggling car market. The overall decline in car sales during COVID-19 is clearly linked to historically low consumer confidence as a result of the pandemic.

But there are also other structural factors at play. For example, during the height of restrictions many car-owning households would not have replaced their cars as normal. During this period the demand for car services – most of which involves getting to work and dropping off the kids – disappeared. And any passengers wanting to take a prospective purchase for a test drive would have run up against social distancing issues.

Over the medium term, other COVID-related changes in living and location decisions may offset part of the decline in 2020 sales. For example, if the current work-from-home trajectory continues, the demand for housing close to the centres of work will decline.

Is the relocating urbanite more likely to buy a new car? Possibly. The demand for cars is higher in low-density rural locations. Plus, cheaper houses in more rural areas means lower mortgage repayments, leaving consumers with greater discretionary income, perhaps enough to cover repayments for a new car.

There are also health factors to consider: the COVID-19 pandemic has led to fear of public transport and a number of recent surveys show a health-related shift to non-public forms of transport, including cars. Many of these factors may partially revert once a vaccine is produced.

Growing popularity

Economic factors are likely to be playing a role in the very large shift to electric vehicles. First, the variety of EVs available has increased, even in the last six months. And each new model appears more and more aligned with the driving needs of the typical family (range, charging and size).

Second, it is possible that the EV buyer segment, who tend to be wealthier, has been less affected by the crisis. Evidence from a different car segment might support this hypothesis: in Germany, for example, the decline in sales of more expensive luxury brands was lower.

In terms of EV prices, while many government COVID-19 recovery packages included more grants for EVs (Germany and France), these changes came too late in the year (June) to explain the above trends.

One final potential driver could be the most important, mainly because it affects all aspects of behaviour and decisions – the extent that the COVID-19 experience increased our concern for the environment. Generally speaking, the more that people know and care about the environment, the more their behaviours reflect this. This also appears to be the case for car decisions: research shows environmental awareness increases the likelihood that a buyer will switch to buying an electric vehicle.

Although there are no studies yet into how the pandemic has (or hasn’t) shifted attitudes in Europe, there is anecdotal evidence that the experience has changed people’s views of their natural environment. Some commentators, for example, highlight a higher appreciation for nature as a result of lockdown restrictions.

It is also possible that the battle against COVID-19 is teaching us something about our connection to society. Community-based measures to stop the virus spreading (social distancing and mask wearing) are largely driven by altruistic motives – that is, personal sacrifices for the benefit of others, most of whom we will never meet. That sounds a lot like the battle against climate change to me.![]()

James Carroll, Research Fellow in Energy Economics, Trinity College Dublin

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.