To explain why the coronavirus pandemic is much worse in the U.S. than anywhere else in the world, commentators have blamed the federal government’s mismanaged response and the lack of leadership from the Trump White House.

Others have pointed to our culture of individualism, the decentralized nature of our public health, and our polarized politics.

All valid explanations, but there’s another reason, much older, for the failed response: our approach to fighting infectious disease, inherited from the 19th century, has become overly focused on keeping disease out of the country through border controls.

As a professor of medical sociology, I’ve studied the response to infectious disease and public health policy. In my new book, “Diseased States,” I examine how the early experience of outbreaks in Britain and the United States shaped their current disease control systems. I believe that America’s preoccupation with border controls has hurt our nation’s ability to manage the devastation produced by a domestically occurring outbreak of disease.

Germ theory and the military

Though outbreaks of yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera occurred throughout the 19th century, the federal government didn’t take the fight against infectious disease seriously until the yellow fever outbreak of 1878. During that same year, President Rutherford B. Hayes signed the National Quarantine Act, the first federal disease control legislation.

By the early 20th century, a distinctly American approach to disease control had evolved: “New Public Health.” It was markedly different from the older European concept of public health, which emphasized sanitation and social conditions. Instead, U.S. health officials were fascinated by the newly popular “germ theory,” which theorized that microorganisms, too small to be seen by the naked eye, caused disease. The U.S. became focused on isolating the infectious. The typhoid carrier Mary Mallon, known as “Typhoid Mary,” was isolated on New York’s Brother Island for 23 years of her life.

Originally, the military managed disease control. After the yellow fever outbreak, the U.S. Marine Hospital Service (MHS) was charged with operating maritime quarantine stations countrywide. In 1912, the MHS became the U.S. Public Health Service; to this day, that includes the Public Health Service Commissioned Corps led by the surgeon general. Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention started as a military organization during World War II, as the Malaria Control in War Areas program. Connecting the military to disease control promoted the notion that an attack of infectious disease was like an invasion of a foreign enemy.

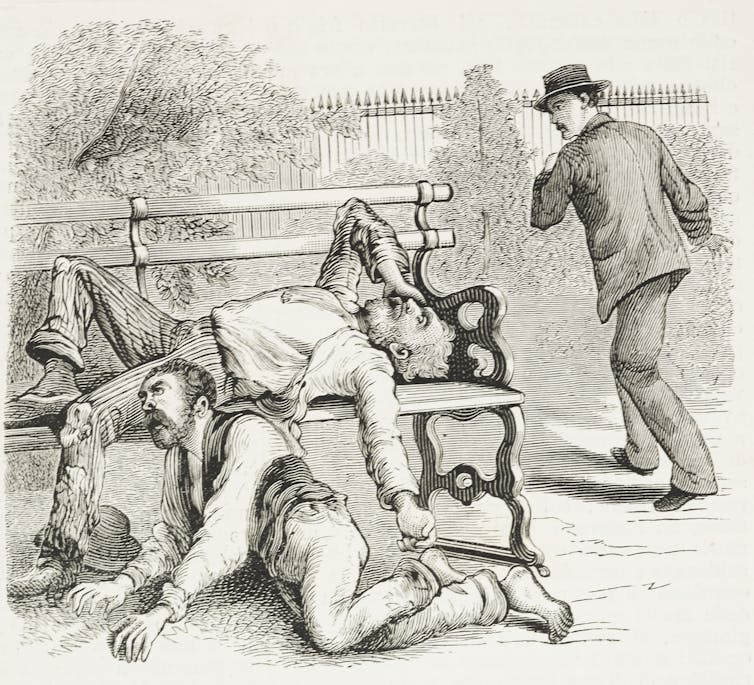

Germ theory and military management put the U.S. system of disease control down a path in which it prioritized border controls and quarantine throughout the 20th century. During the 1918 influenza pandemic, New York City held all incoming ships at quarantine stations and forcibly removed sick passengers into isolation to a local hospital. Other states followed suit. In Minnesota, the city of Minneapolis isolated all flu patients in a special ward of the city hospital and then denied them visitors. During the 1980s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service denied HIV-positive persons from entering the country and tested over three million potential immigrants for HIV.

Defending the nation from the external threat of disease generally meant stopping the potentially infectious from ever entering the country and isolating those who were able to gain entry.

Our mistakes

This continues to be our predominant strategy in the 21st century. One of President Trump’s first coronavirus actions was to enforce a travel ban on China and then to limit travel from Europe.

His actions were nothing new. In 2014, during the Ebola outbreak, California, New York and New Jersey created laws to forcibly quarantine health care workers returning from west Africa. New Jersey put this into practice when it isolated U.S. nurse Kaci Hickox after she returned from Sierra Leone, where she was treating Ebola patients.

In 2007, responding to pandemic influenza, the Department of Homeland Security and the CDC developed a “do not board” list to stop potentially infected people from traveling to the U.S.

When such actions stop outbreaks from occurring, they are obviously sound public policy. But when a global outbreak is so large that it’s impossible to keep out, then border controls and quarantine are no longer useful.

This is what has happened with the coronavirus. With today’s globalization, international travel, and an increasing number of pandemics, attempting to keep infectious disease from ever entering the country looks more and more like a futile effort.

Moreover, the U.S. preoccupation with border controls means we did not invest as much as we should have in limiting the internal spread of COVID-19. Unlike countries that mounted an effective response, the U.S. has lagged behind in testing, contact tracing, and the development of a robust health care system able to handle a surge of infected patients. The longstanding focus on stopping an outbreak from ever occurring left us more vulnerable when it inevitably did.

For decades, the U.S. has been underfunding public health. When “swine flu” struck the country in 2009, the CDC said 159 million doses of flu shots were needed to cover “high risk” groups, particularly health care workers and pregnant women. We only produced 32 million doses. And in a pronouncement that now looks prescient, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report said if the swine flu outbreak had been any worse, U.S. health departments would have been overwhelmed. By the time Ebola appeared in 2014, the situation was no better. Once again, multiple government reports slammed our response to the outbreak.

Many causes exist for the U.S.‘s failed response to this crisis. But part of the problem lies with our past battles with disease. By emphasizing border controls and quarantine, the U.S. has disregarded more practical strategies of disease control. We can’t change the past, but by learning from it, we can develop more effective ways of dealing with future outbreaks.![]()

Charles McCoy, Assistant Professor of Sociology, SUNY Plattsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.