Politics, like everything else in American life, is being reshaped by the pandemic and by technology. Democrats held almost all of their 2020 nominating convention virtually. Republicans have not moved their convention online – delegates will still attend the event in Charlotte, North Carolina – but it will be significantly scaled back.

Most notably, President Donald Trump will give his renomination acceptance speech at another location – first planned to be in Jacksonville, Florida, but which now might be at the White House, or possibly the Gettysburg battlefield, but which could theoretically happen anywhere.

These technological adaptations signal a permanent shift in the way nominating conventions meet and the way voters watch them – but it’s not the first time such radical changes have come to politics.

Technology has driven change in the presidential nominating process since the earliest days of American parties. This is a lesson I learned while researching 19th-century party politics for my book, “The Nationalization of American Political Parties, 1880-1896.” America’s current party organizations were built as party leaders used new technologies to make their proceedings more attractive to voters and their candidates more appealing.

The caucus system

The first nominating process was not a convention at all. In an age of horse-drawn carriages on muddy dirt roads it could take more than a week – in good weather – just to cross large states like New York. Travel was expensive and unreliable, making large gatherings of people separated by great distances unworkable. So the earliest party nominations in 1796 and 1800 happened when members of Congress started consulting in informal meetings called caucuses to select nominees before returning home for fall campaigns. It was an efficient means of achieving party unity under the circumstances. There was, however, little room for voter involvement.

Between 1800 and 1830, states built better roads and canals. Travel times were shortened, and the cost of travel shrunk. The Post Office, established in 1792, delivered printed material cheaply, subsidizing a booming national press. Americans were able to gather across vast distances, had better information and depended less on word of mouth from political leaders.

The rise of conventions

With better informed citizens, the caucus system was in disarray by the 1820s. It was fully discredited in the eyes of many voters and political elites in 1824 when less than half of the members of the Republican party caucus attended the meeting. Multiple nominees were instead selected by state legislatures, creating a crisis of legitimacy for the dominant Republican party, which historians now refer to as the Democratic-Republican party.

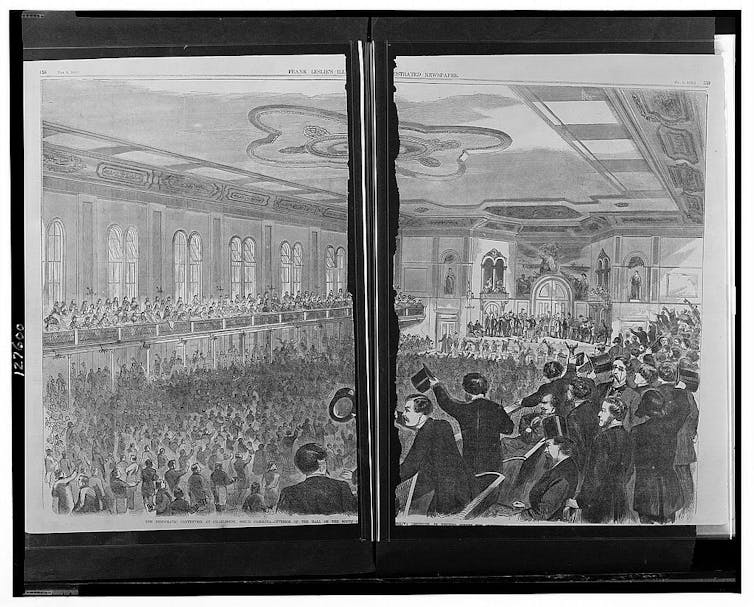

In 1828, Andrew Jackson won the presidency, based in part on a nomination from the Tennessee state legislature. After his victory, he engineered the first national convention of a major party in 1832, at which the Jackson faction of the Republican party called itself the Democratic party.

The convention did not officially re-nominate Jackson, but it did choose his running mate, Martin Van Buren. In the process it demonstrated that a national convention could in fact gather larger numbers of delegates, who themselves represented a larger number of voters, and could therefore be more democratic.

This convention model dominated American politics for the next hundred years.

Convention sites followed the progress of American transportation networks westward. The first six Democratic national conventions were held in Baltimore due to its convenient location and its position on the border of slave and free states. But as railroads made travel less expensive, the parties moved west. In 1856 Democrats convened in Cincinnati, in 1864 in Chicago, and in 1900 in Kansas City, Missouri.

Republicans met in Chicago as early as 1860 and as far west as Minneapolis by 1892. To appeal to different regions, both parties moved their conventions every four years – a tradition maintained to this day.

Conventions in the 20th century

Another technological shift came in 1932, when Franklin Roosevelt became the first major party nominee to address a convention in person.

Until then, custom dictated that the nominee stayed home under the pretense of not being too ambitious for office. Some months later, a committee of delegates would visit the nominee to “inform” him of his candidacy. Only then did the nominee give brief prepared remarks and start actively campaigning.

Roosevelt blew through that custom by catching a plane from New York to the Democratic convention site in Chicago and addressing the delegates the day after his nomination. “Let it be from now on the task of our party to break foolish traditions,” Roosevelt intoned, before calling for a “new deal.”

Traveling to Chicago was not just a metaphor for Roosevelt. By dominating the attention of the convention at precisely the time voters were paying attention to it, FDR signaled his intention to not only be a nominee of the party, but the leader of the party. And it made his transformative political message part of the news.

Television further changed the conventions. For much of the 19th century, presidential nominations were contested by multiple candidates, causing difficult convention battles; the 1924 Democratic convention went through 103 rounds of balloting before settling on John W. Davis.

Starting in 1948, conventions permitted television cameras, which reduced the incentives for endless ballots. Instead, conventions became visible celebrations of party unity.

In 1972, the parties started using primary elections to select delegates pledged to vote for specific candidates, so the delegate count was publicly known before the conventions were gaveled to order. Conventions became days-long infomercials for the nominee.

Unconventional conventions

The pandemic has struck at just the right moment for another technological shift. Network television news – the medium through which most 20th century conventions were viewed – commands less voter attention.

Moving the convention spectacle online allows the party to control their message more effectively – as Republican efforts to exclude journalists from the proceedings highlight.

Democrats recorded some speeches in advance, allowing the party to release focused content compatible with the pace and packaging of social media. As voters share and comment on that content, using official party social media graphics and Zoom screens, it could nurture a sense of party identification, and of virtual participation.

What comes next?

The GOP’s wavering between different locations, and the Democrats’ reliance on remote speakers, will lead some to ask whether a centralized convention is even necessary. In the future, why not have multiple convention sites across the country, with multiple political figures speaking to smaller physical audiences?

Events like that could enable the party to target narrow groups of voters more effectively. As parties experiment with the potential of digital technologies, it seems likely that they will find some of them more attractive than cavernous convention halls and outdated swarms of straw hats.

But that approach would have disadvantages. Social media spectacles would eliminate spontaneous reactions from delegates that give home viewers a sense of the mood – whether dissension from the party line, contagious enthusiasm or even the striking power of a memorable speech line. Democrats have acknowledged that the online format in 2020 will deprive supporters of Bernie Sanders the stage they had in 2016. As much as specialized events might draw in some voters by targeting narrow groups, they might also allow parties to create more divisive appeals in ways that evade broader scrutiny. And virtual conventions can make it easier for party leaders to obscure proceedings from journalists and the public.

It’s not yet clear how this moment will reshape nominating conventions. But party leaders will adapt to the technological opportunities it presents, and find new ways to make conventions work.![]()

Daniel Klinghard, Professor of Political Science, College of the Holy Cross

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.