After COVID-19, some city streets might never revert to how they were before the lockdown.

Global-scale lockdowns have emptied the city streets. With cars staying parked and public transportation mostly absent, some noticeable effects have been observed:

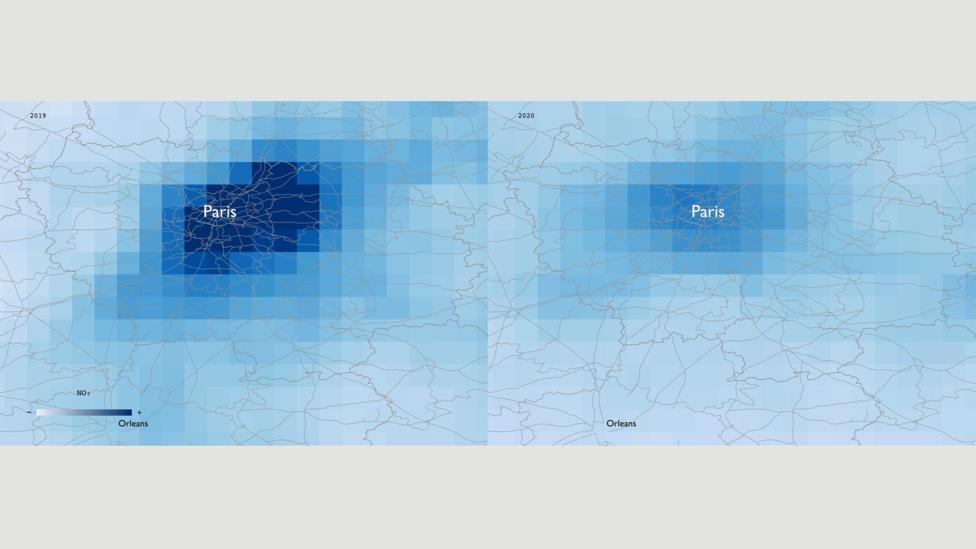

- Air quality has improved significantly, as seen in cities like France and Wuhan through satellite imagery.

- With lowered demand for oil combined with political tension, a price war began between Russia and Saudi Arabia. Never before seen spikes have also occurred.

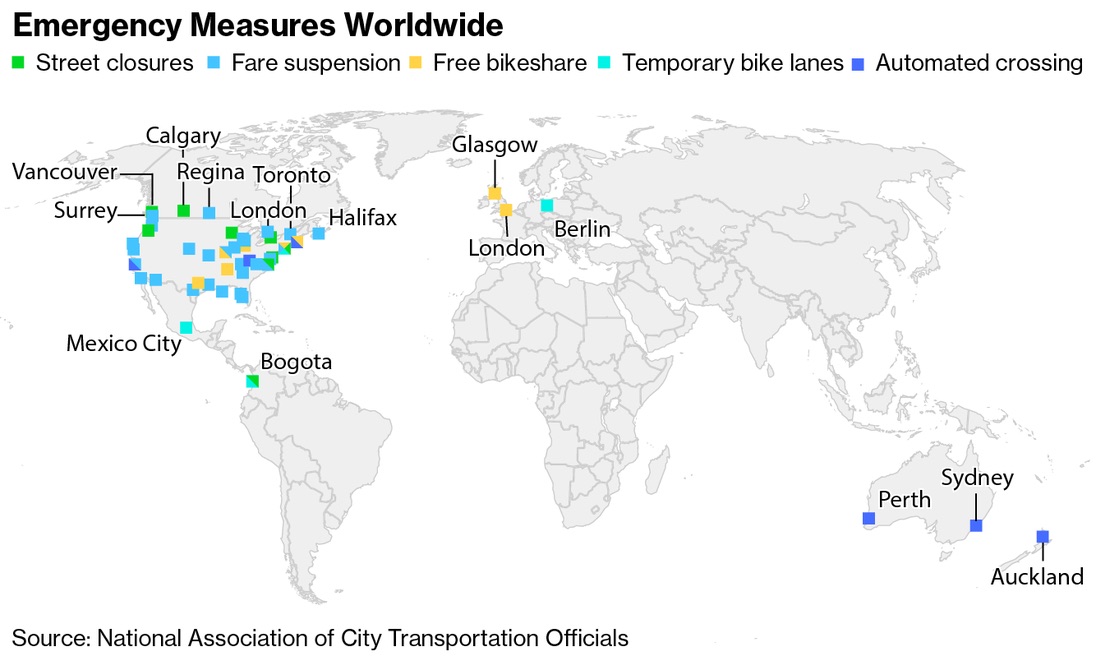

- There is an increase in walking and cycling as modes of mobility to enable social distancing between residents. This is supported by an expansion of cycling and walking zones in cities like New Zealand, Scotland, Mexico, and New York.

Some of the changes from the emptying of the streets are unfortunate, but a lot of them are desirable even in a pandemic-free world. However, most of these desirable effects will disappear once the lockdowns have eased and cars have returned to action.

With this, some city planners are taking this as a rare opportunity to possibly change the course of mobility for good.

Milan

Milan is the epicentre of the outbreak in Italy. Apart from a large number of confirmed cases in the city, Milan is also among the most polluted cities in Europe.

The COVID-19 lockdown has brought down both the number of cars and air pollution in Milan. After the pandemic, officials are eyeing not only to prevent the resurgence of COVID-19 cases but also pollution.

To do this, Milan announced the Strade Aperte (Open Roads) plan, which involves the instalment of temporary bike lanes, widened pavements, tighter speed restrictions, pedestrian- and cyclist-priority lanes, and the creation of 35 kilometres of new cycle routes.

“Of course, we want to reopen the economy, but we think we should do it on a different basis from before.” according to Milan deputy mayor, Marco Granelli.

Granelli said that cars take up the space the people can use to move around and take advantage of for commercial activities.

Paris

Meanwhile in Paris, also among the hardest hit during the pandemic, Mayor Anne Hidalgo said that returning to the car-filled condition of the Paris streets is left out of consideration.

“Pollution is already in itself a health crisis and a danger — and pollution joined up with coronavirus is a particularly dangerous cocktail. So it’s out of the question to think that arriving in the heart of the city by car is any sort of solution when it could actually aggravate the situation.,” Hidalgo said.

Among the initial steps taken by Hidalgo include the creation of new bike lanes which encompasses the city’s centre and extends to the suburban area. Even before the pandemic, a lot of these tracks have already been in place as a part of her anti-car programme aiming to decimate the city’s carbon footprint.

Apart from Paris and Milan, measures like these have been implemented in cities like Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, and Mexico.

The permanency of these measures remains unclear. However, these initiatives serve as proof that guiding city mobility towards sustainability is not as out of reach as it may seem at first glance.