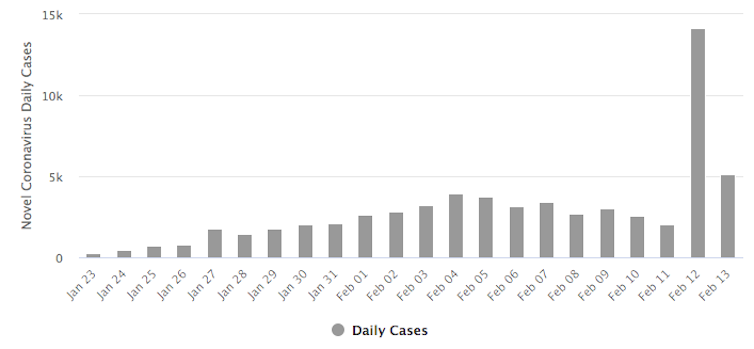

Investors are still being fairly complacent about the novel coronavirus. After the number of new daily cases suddenly shot up to more than 15,000 on February 12 following more than a week of decline, there were some jitters in the markets. With Chinese authorities saying the increase was due to a decision to broaden the definition for diagnosing people, there were falls in the region of 1% in European markets, and smaller retrenchments in Asia and North America.

It is a fairly minor shift in sentiment after a few days in which investor concerns had been steadily receding. There appears to be a real danger of underestimating the likely economic impact of this crisis. China’s manufacturing sector in particular faces an unprecedented challenge because supply chains have been so seriously disrupted.

Coronavirus daily new cases

Well over 80 cities have gone into lockdown, including the entire areas of five Chinese provinces – Hubei, Liaoning, Jiangxi, An’hui and Inner Mongolia – and four main cities in Zhejiang province, affecting well over 275 million people. Since February 10, Beijing and Shanghai have further restricted the movement of people, having already extended the Chinese New Year break.

My parents live in Jiangxi province and are among millions semi-quarantined at home. The local government allows one person from each household to go out every two day to buy necessities. Even in cities not under compulsory lockdown, there are rarely people on the streets. The tweet below shows the Nanjing Road in Shanghai, the busiest shopping precinct in the country. It was taken on January 26 but the situation is not much better now.

This is taking a serious toll on the Chinese economy. No statistics on the actual losses are available yet, but for example, the number of intercity passengers on public transport during the new year break was only 60% of 2019 levels.

Xibei, a famous dining brand with 350 restaurants and RMB5.7 billion (£628 million) annual revenues, said takings during the holiday period were down 87% year on year. The contrast with last year, when Chinese tourism, retail and catering revenues all rose by around 8% during the new year period, is likely to be huge.

The problems in the Chinese services sector are primarily a demand shock. This will probably rebound once the epidemic is contained, just like during the Sars outbreak of 2003. The Chinese inflation rate based on the consumer price index (CPI) turned down during peak crisis between February and June 2003, then quickly shifted to positive.

Makers not marching

This time around in manufacturing, which comprises nearly a third of the Chinese economy, there is a much bigger shock to the supply side than in 2003. Factory lines have ground to a halt because of the lockdown. You can see the gap between the demand and supply of Chinese goods by comparing the inflation rate with the level of optimism among the country’s manufacturers, as measured by the purchasing managers’ index (PMI).

The Chinese CPI in January rose 5.4%, the highest monthly rate since October 2011, while the manufacturing PMI hit a three-month low of 50%. The fact that inflation is actually rising this time when it fell in 2003 is because this time, both supply and demand are falling but supply is falling faster.

To keep the economy afloat, the government has rolled out a series of financial measures, including lower borrowing rates, loan extensions, tax reductions and waivers, and an injection of RMB200 billion (£22 billion) in market liquidity. This will ease financial strains, but not address the underlying problems in manufacturing supply chains.

Many manufacturers cannot resume work because they can’t get supplies of raw materials and their workforce is quarantined. They are having problems with orders, wage payments, cash flow, order deliveries, debt repayments, and logistics and transport. Many are also facing penalties for breaching contracts.

Many companies are also having to suspend operations by order of the local government. For example, out of 29,814 firms that have applied to resume operations in Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang province, just 162 had been given authorisation by February 10.

Many smaller companies can’t get authorisation because they are less capable of sourcing face masks than bigger companies. They are also more wary of letting out-of-town workers return because they usually have less dormitory space so can’t give them a room to themselves – another key precaution against the spread of infection.

A poll of 1,295 firms by the Chinese Academy of Social Science (CASS) published on February 1 found that 43.9% expected their business will post a loss in the coming year. It won’t take long before liquidity problems morph into solvency problems, especially for smaller companies. Only 9% of respondents to the CASS survey thought they would survive a month of suspended operations, while two-thirds said that a two-week shutdown was all they could take.

Global supply chains

This is already disrupting the world supply chain for manufacturing, hitting everyone from big South Korean car manufacturers like Hyundai and Kia to small tech companies in the US like Agilian Technology.

Some Chinese manufacturers, such as number-one Apple supplier Foxconn, are resuming work in phases, but they still need more time to reach full capacity because only local employees can return immediately. Workers travelling from elsewhere have to isolate themselves at home for seven to 14 days before returning. The next Apple smartphone, due in March, could be delayed.

The new coronavirus is a major shock to all market participants in China. Even if the outbreak is contained over the next few weeks, it will still have a long-term impact. The demand and supply shocks could combine to drive China into stagflation, where there is inflation and weak economic growth at the same time, and for which there are no effective monetary or fiscal policies.

The uncertainty created by the outbreak, compounded by China’s trade war with the US, is going to force companies to re-examine their exposure to Chinese manufacturing and the whole idea of a global supply chain. It wouldn’t be surprising to see rival countries developing supply hubs of closely linked manufacturers of the kind that China has created very successfully. This, too, looks like bad news for China. The novel coronavirus is prompting a new period of global instability whose ramifications could be felt for many years to come.![]()

Chusu He, Lecturer in Finance, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.