Despite efforts to encourage a shift to sustainable transportation, traffic congestion is often the focus of debates over mobility. Global demand for automobiles rose significantly in the 1990s, with annual sales stabilising at close to 80 million vehicles since 2017. Faced with the flood of cars, for decades governments have attempted to improve mobility of citizens – some measures focus on widening existing roads and building new ones, while others encourage a switch to alternatives such as public transportation, cycling and walking.

What lessons can be learnt from experiences of different cities in their attempt to deal with traffic congestion?

Increasing road space – does it solve the problem?

In simple words, congestion occurs when demand for road space exceeds supply.

Hence, building new roads or adding more lanes to existing ones might seem as obvious solutions. It surely sounds logical enough: as cities grow bigger, roads serving them should follow the same trend. Drivers should have more space to move if they have wider or new roads, which relieves congestion and makes cars go faster. This argument is frequently used by government officials to elaborate on the importance of new and frequently costly infrastructure projects.

However, it hasn’t always turned out this way in practice, and the reasons behind could be found in long-term effects of the induced demand. The term “induced demand” refers to the situation where as supply of a good increases, more of that good is consumed. This implies that new roads essentially create additional traffic, which in turn causes them to become congested all over again.

Why does this happen? After a new highway is added or an existing one widened, initially there are fewer traffic jams and trips become quicker. However, these improvements change people’s behaviour. Drivers who had previously avoided that route because of congestion now consider it as an attractive choice. Others who previously used public transportation, bicycles or other modes of transportation may shift to using their cars. Some people might change their time of travel – instead of travelling in off-peak times to avoid congestion, they start travelling in peak-times, increasing congestion. Hence, as more people start using the highway, initial time-saving effects are reduced and eventually disappear.

Katy Freeway in Houston, Texas, illustrates this problem. With its 26 lanes, it is considered as the widest highway in North America. The expansion project was completed in 2011 and cost US$2.8 billion. Not long after, however, congestion actually worsened. A 2014 analysis by City Observatory found that compared to 2011 levels, morning commute times increased by 30%, while afternoon commute times increased by 55% – so much for reducing congestion.

Reducing and relocating road space

When looking at top ten cities for time lost due to congestion in 2018, eight are European. One common factor impacting congestion in Paris, London, Rome, Milan or Barcelona is their age. Some roads predate the arrival of cars, increasing the complexity of road projects. In fact, car-centric infrastructure in a sense collides with ancient street patterns, public transit and walking development patterns.

At the same time, European cities tend to be most progressive when it comes to reducing and relocating road space to make room for other types of transportation. Zurich, for example, deliberately slowed its road traffic down to make itless popular, while Paris has pursued a policy of expanding space dedicated to buses, bicycles and pedestrians, while reducing that once turned over exclusively to cars.

Let’s look at solutions of London more closely…

Battle to tackle London congestion continues

In 2003 the city of London implemented a congestion charge in the attempt to turn away motorists from driving to other means of travel. It functions on a fairly simple basis: vehicles entering the Congestion Charging Zone of central London from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. on a weekday are now charged a flat daily fee of 11.50 pounds (13 euros). Coupled with other actions, several important contributions were achieved.

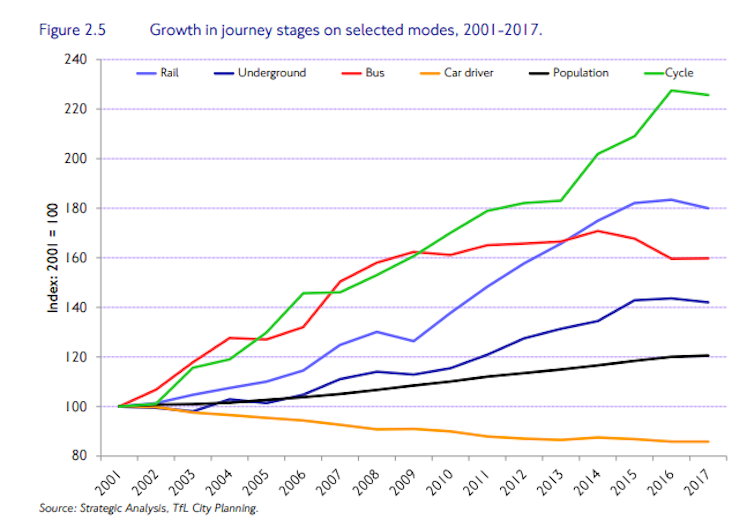

Traffic volume in the charging zone in 2017 remained 22% lower in comparison to a decade earlier. Number of private cars entering inner-city London fell by 39% between 2002 and 2014. Simultaneously, a well-established shift toward public transportation is evident. In 2017, 45% of journey stages in London were attributed to travelling by bus, tram, underground and rail – an increase of 10.5% compared to early 2000s. Additionally, cycling experienced significant growth, with 727,000 trips made per day in 2016 – a jump of 9% in comparison to 2015.

But London’s congestion charge has been showing signs of age. Traffic speeds are slower, journey times are longer. With 227 hours lost per driver in 2018, London ranked as the 6th city in the world for time lost in traffic.

Several factors have contributed. The boom in online shopping increased the number of delivery vans on London’s streets: in 2012 they drove 3.8 billion kilometres, and in 2017, 4.8 billion – a 26% rise. Also, private-hire services such as Uber have seen an explosion in the number of registrations – up 75% from 2013 to 2017. Another challenge is the reduction in road space. Road capacity for motorists is reduced due to temporary construction work in some areas, as well as the road space relocation aimed to improve facilities for cyclists, pedestrians and taxis.

While Londoners can be optimistic when it comes to alternatives to driving being developed, improving driving experience will be a more challenging task to achieve without some major reconsideration of the current charging system.

Currently, two adjustments have been introduced that should bring some improvement. Private-hire vehicles will no longer be exempt from paying the congestion charge if they travel within the zone during peak hours. Also, an Ultra-Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) was put in place for the same area as the Congestion Charging Zone, aiming to improve air quality. Vehicles entering the zone that don’t meet exhaust emission standards will pay additional 12.50 pounds (14.10 euros). Still, as more electric vehicles hit the streets, the positive effects of ULEZ will likely decrease over time…

Inspiration from Singapore

Over previous decades, population density in the city-state of Singapore has soared, reaching 8,000 inhabitants per km2 in 2017 – a 75% rise compared to 1990s Even so, it continues to experience less traffic congestion and faster driving speeds in comparison to many of its neighbours. Singapore authorities had a rather innovative approach to managing road usage and have implemented a set of aggressive anti-congestion policies.

Car ownership is controlled through quota system introduced in 1990s. Car buyers bid for Certificate of Entitlement (COE) – the right to car ownership and usage of road space. Its cost is determined by demand and supply for vehicles, meaning that if demand is high, COE could become more expensive than the car itself. However, this measure showed some limitations. Many people felt that as long as they are paying such a high cost for driving, they should use their car as much as possible – hence the traffic congestion worsened.

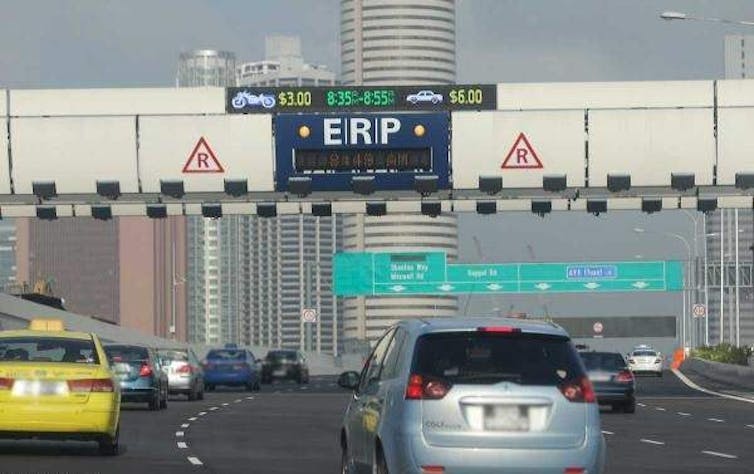

Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) system implemented in 1998 was a breakthrough. It functions on the “pay as you use” principle to manage traffic demand. ERP platforms equipped with sensors and cameras are positioned at entry points to particular zones of the city. Each car has an in-vehicle unit with a cash card. When passing through the platforms, drivers are charged different rates depending on the time of the day and the level of congestion on roads. This makes them reconsider their time of travel, route or transportation mode.

Additionally, a 190-kilometre-long mass rail transit (MRT) system with subsidised fares has been developed. Trains are known to be comfortable, clean and frequent, and stations are air-conditioned. New housing was built in the proximity of the MRT stations, which makes commuting even more convenient.

Looking ahead, Singapore continues exploring “smart solutions” to improve commuting experience and achieve even smoother rides. Some of the anticipated projects include on-demand transport and driverless shuttles, hands-free fare gates, account-based ticketing, LED strips at pedestrian crossings, and new MTR lines.

Also, satellite-based system of road pricing is scheduled for 2020 and will upgrade the current ERP. Technology advancements allow more sophisticated traffic monitoring. For example, a variety of fixed and mobile enforcement cameras will be used to collect information about congestion, optimise traffic management (for example, traffic-lights timing), and offer more services to motorists. The upgrade will not come cheap though – it requires an investment of the equivalent of 392 million US dollars.

New York introduces congestion charge

Following the example of London, in 2021 New York will become the first US city to implement congestion pricing for select zones of Manhattan. The measure has been long discussed and disputed, with various proposals surfacing and dying regularly over the last 10 years. Why? Congestion charges are politically challenging to undertake, to say the least.

In the case of New York, congestion charging is intended to address several worrying indicators. As of 2018, average car speed has fallen to 4.7 mph, which is only slightly faster than walking.

The administration of Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that the funds obtained from the congestion charge would provide sustainable funding source of 15 billion US dollars over a period of 5 years, desperately needed to improve and modernise New York’s subway system. Its on-time performance is still reported as 13% worse than in 2012, due to maintenance delays and dated infrastructure.

Looking ahead…

Experiences of different cities show that addressing the challenge of traffic congestion requires an integrated transportation-policy approach, which takes into account a number of factors and individual circumstances they face.

It is clear that developing attractive, affordable, comfortable and reliable alternatives to driving are indispensable. Additionally, constant revisions and updates of policies are required, as their effects tend to wear off over time – therefore, dynamic approach is needed. New technologies and “smart” solutions will lead the way forward, but they require significant investment, which many governments might struggle with.

In the meantime, people need to move and go to work. The question is how they do it, and much time they lose along the way.![]()

Jovana Stanisljevic, Professor in International Business, Department People, Organization, Society, Grenoble École de Management (GEM)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.