What if globally designed products could radically change how we work, produce and consume? Several examples across continents show the way we are producing and consuming goods could be improved by relying on globally shared digital resources, such as design, knowledge and software.

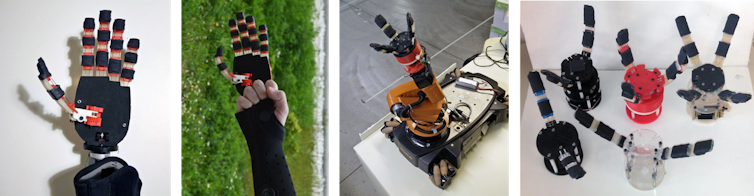

Imagine a prosthetic hand designed by geographically dispersed communities of scientists, designers and enthusiasts in a collaborative manner via the web. All knowledge and software related to the hand is shared globally as a digital commons.

People from all over the world who are connected online and have access to local manufacturing machines (from 3D printing and CNC machines to low-tech crafts and tools) can, ideally with the help of an expert, manufacture a customised hand. This the case of the OpenBionics project, which produces designs for robotic and bionic devices.

There are no patent costs to pay for. Less transportation of materials is needed, since a considerable part of the manufacturing takes place locally; maintenance is easier, products are designed to last as long as possible, and costs are thus much lower.

Take another example. Small-scale farmers in France need agricultural machines to support their work. Big companies rarely produce machines specifically for small-scale farmers. And if they do, the maintenance costs are high and the farmers have to adjust their farming techniques to the logic of the machines. Technology, after all, is not neutral.

So the farmers decide to design the agricultural machines themselves. They produce machines to accommodate their needs and not to sell them for a price on the market. They share their designs with the world – as a global digital commons. Small scale farmers from the US share similar needs with their French counterparts. They do the same. After a while, the two communities start to talk to each other and create synergies.

That’s the story of the non-profit network FarmHack (US) and the co-operative L’Atelier Paysan (France) which both produce open-source designs for agricultural machines.

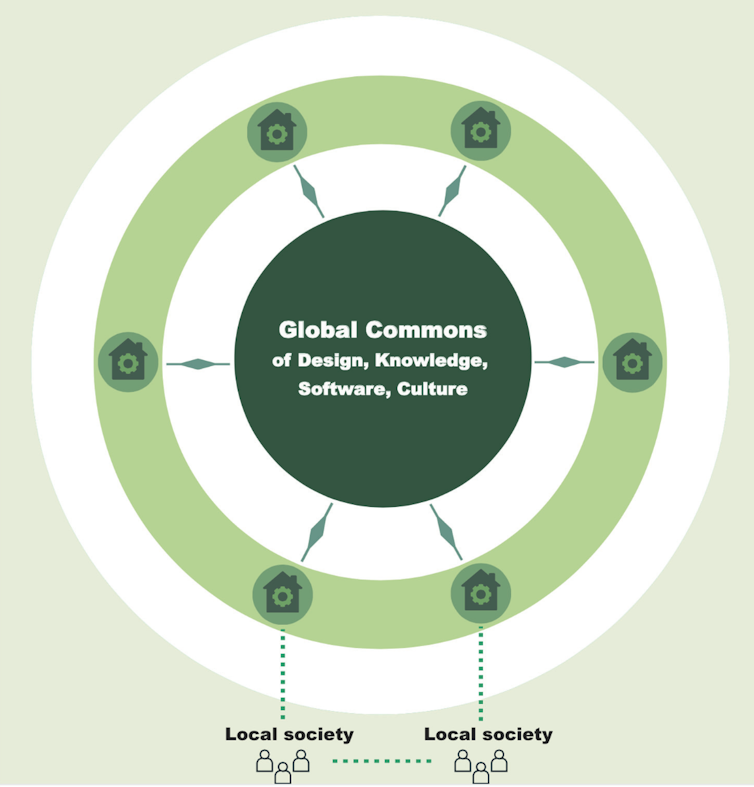

With our colleagues, we have been exploring the contours of an emerging mode of production that builds on the confluence of the digital commons of knowledge, software, and design with local manufacturing technologies.

We call this model “design global, manufacture local” and argue that it could lead to sustainable and inclusive forms of production and consumption. It follows the logic that what is light (knowledge, design) becomes global while what is heavy (manufacturing) is local, and ideally shared.

When knowledge is shared, materials tend to travel less and people collaborate driven by diverse motives. The profit motive is not totally absent, but it is peripheral.

Decentralised open resources for designs can be used for a wide variety of things, medicines, furniture, prosthetic devices, farm tools, machinery and so on. For example, the Wikihouse project produces designs for houses; the RepRap community creates designs for 3D printers. Such projects do not necessarily need a physical basis as their members are dispersed all over the world.

Finding sustainability

But how are these projects funded? From receiving state funding (a research grant) and individual donations (crowdfunding) to alliances with established firms and institutions, commons-oriented projects are experimenting with various business models to stay sustainable.

These globally connected local, open design communities do not tend to practice planned obsolescence. They can adapt such artefacts to local contexts and can benefit from mutual learning.

In such a scenario, Ecuadorian mountain people can for example connect with Nepalese mountain farmers to learn from each other and stop any collaboration that would make them exclusively dependent on proprietary knowledge controlled by multinational corporations.

Towards ‘cosmolocalism’

This idea comes partly from discourse on cosmopolitanism which asserts that each of us has equal moral standing, even as nations treat people differently. The dominant economic system treats physical resources as if they were infinite and then locks up intellectual resources as if they were finite. But the reality is quite the contrary. We live in a world where physical resources are limited, while non-material resources are digitally reproducible and therefore can be shared at a very low cost.

Moving electrons around the world has a smaller ecological footprint than moving coal, iron, plastic and other materials. At a local level, the challenge is to develop economic systems that can draw from local supply chains.

Imagine a water crisis in a city so severe that within a year the whole city may be out of water. A cosmolocal strategy would mean that globally distributed networks would be active in solving the issue. In one part of the world, a water filtration system is prototyped – the system itself is based on a freely available digital design that can be 3D printed.

This is not fiction. There is actually a network based in Cape Town, called STOP RESET GO, which wants to run a cosmolocalisation design event where people would intensively collaborate on solving such a problem.

The Cape Town STOP RESET GO teams draw upon this and begin to experiment with it with their lived challenges. To make the system work they need to make modifications, and they document this and make the next version of the design open. Now other locales around the world take this new design and apply it to their own challenges.

Limitations and future research

A limitation of this new model is its two main pillars, such as information and communication as well as local manufacturing technologies. These issues may pertain to resource extraction, exploitative labour, energy use or material flows.

A thorough evaluation of such products and practices would need to take place from a political ecology perspective. For example, what is the ecological footprint of a product that has been globally designed and locally manufactured? Or,to what degree do the users of such a product feel in control of the technology and knowledge necessary for its use and manipulation?

Now our goal is to provide some answers to the questions above and, thus, better understand the transition dynamics of such an emerging mode of production.![]()

Vasilis Kostakis, Senior Research Fellow at Tallinn University of Technology, Affiliate at Berkman Klein Center, Harvard University and Jose Ramos, Lecturer, Globalisation Studies, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.